Which strings shall I try on my Violoncello da Spalla? (part 3)

Where to start in our search for the perfect Violoncello da Spalla set of strings?

Following from:

If you liked the podcast version and the possibility to listen to this newsletter, using the Substack app you can have this article read by an automatic voice, which is quite good, I believe, better than me reading a text in what for me is a foreign language. As this is a bit of a techy topic, which needs a few “slides”, I prefer it in this format. I value your feedback, so let me know in the comments which version you prefer and if the automatic voice is usable enough for you.

A completely different factor to consider is how historically correct you would like to be regarding the instrument itself.

I’m not speaking strictly about the HIP movement here, neither I’m speaking about which repertoire is correct playing with Violoncello da Spalla or not, if playing da Spalla is plausible at all, if it ever had a role in the continuo group or was used exclusively for obbligato parts. I’m instead speaking about the original voice of the instrument.

When we consider the Violoncello da Spalla as regularly in use between the second half of the 17th century and the second half of the 18th century, if I want to hear the voice it had in those times, which strings should I use?

When I tried our first da Spalla in 2019, I wanted to be historically correct to hear all of its possibilities between its birth and today’s Thomastick modern strings. So, I did my usual when stringing an instrument: I found a first string I liked (trying slightly different diameters and considering tension, sound, feeling and response under the bow). Taking that one as a start, I calculated the second and the third.

Watch a video with a demonstration of this process

I ended up with a 220 third, which was hard to play well, it was hard to find a plausible curve of the bridge as the adjacent strings were much thinner, and all in all, it made the whole instrument feel convincing. I was thinking at the Violoncello da Spalla as a small cello with a string on top, so I wanted it with only two overspun basses and three plain gut trebles. Then, deluded by the result, I succumbed to the evidence and made an appointment at Aquila Strings to have some basses made. Mimmo Peruffo was so kind to let me go there, even if he was on holiday, and work with Hicham, Aquila’s expert employee who substituted me and whom I trained before leaving the company ten years ago.

That day we made a good set with 3 basses and 2 guts, but still, I felt somewhat defeated as I had to accept a wound third. After a closer look at the results, a simple piece of evidence became clear: the set we made corresponded precisely to the light tension set for cello, being all 4 cello strings the upper 4 of the Violoncello da Spalla.

In other words, if you take a usual-size cello and you stop it with your thumb in the fourth position, as a capo, you get something as long as a Violoncello da Spalla, which is playing at the same tuning of the first 4 strings of the Violoncello da Spalla, using the same strings of a regular size cello. This is so convenient! In the 18th century, they didn’t have polishing machines, and strings were not sold per gauge but per number of strands of gut employed in making them. They were not buying, for example, a cello A, but a bundle of 30 strings with everything between 104 and 128 cents of mm in it. (In this bundle, most strings were between 116 and 120, but they also got all the rest.) If they made the small cello as short as our Violoncello da Spalla, they could tune it as a tenor, GDAE, and use the same strings they used on the bigger cello!

This is how I realised that the Violoncello da Spalla is not a small cello with one more string on top but a regular tenor cello with a bass added. So it’s not 2 wound + 3 pure guts, but 3 wound basses + 2 pure gut trebles! This made sense and was something one could play in front of an audience!

That one extra bass string could be made using a double-wound string or not. Even a single wound is possible. In the repertoire of its lifetime, it's the string less used, often even not at all.

Realising this also made me understand why this length works so well for the instrument. Why does the Violoncello da Spalla play with a full tone despite being so small? Because this is the natural given length of a tenor, not only because you can play it horizontally and use violin fingerings!

Great, but where do I start from searching for MY strings and MY voice on the Violoncello da Spalla?

Do I want to play only baroque repertoire or also romantic and modern, or contemporary? In the first case, better try guts. In the second, the choice is still open, from guts to modern.

If I play contemporary music (whether classical, jazz, folk or whatever else you like), do I want a “vintage” crispy sound? If so, I may like to try gut strings.

I don’t want any issue at all with strings; they are something I shouldn’t worry about and possibly never even change them: Thomastick are my choice.

I want that velvet voice, even throughout the whole instrument, like in old 20th-century recordings: Thomastick are my choice.

I want more colours. I want to stand out and find different voices: warm, crispy and everything in between: try gut strings or try modern alternatives like modern Aquila’s or modern Boussoir’s.

This is why we always settle our instruments first with gut strings: because we feel they are the most versatile strings. However, many people just don’t feel at home with them, so we can introduce them the many valid alternatives. What we don’t recommend at all is to mix and match between historical and modern sets. It’s a matter of tension, of colours, of the small tweakings the string maker puts in the game to get you a good, reliable product. Don’t use gut basses with modern first and second. If you don’t want pure gut, and you like modern steel (or aluminium wound) first and second, there are basses made specially to match with them and give you a consistent voice throughout the instrument, respecting the balance of the bridge forces and your instrument. A bridge with five strings is much more susceptible to tension variations than a four-string one. You may find a second string you love but completely kills the fourth, for example, and you’d get crazy in sorting out that the trouble was in the second not well matched instead of in a poor fourth!

Don’t start by changing one string at a time mixing different sets: at first, try complete sets and understand which is closer to your voice. There’s science and experience behind a set, not just maths. Today, unlike in the past, when only gut and silver were available, there are endless combinations of materials to get to that math, but they all give a different voice.

Further readings:

Updates from our workshop

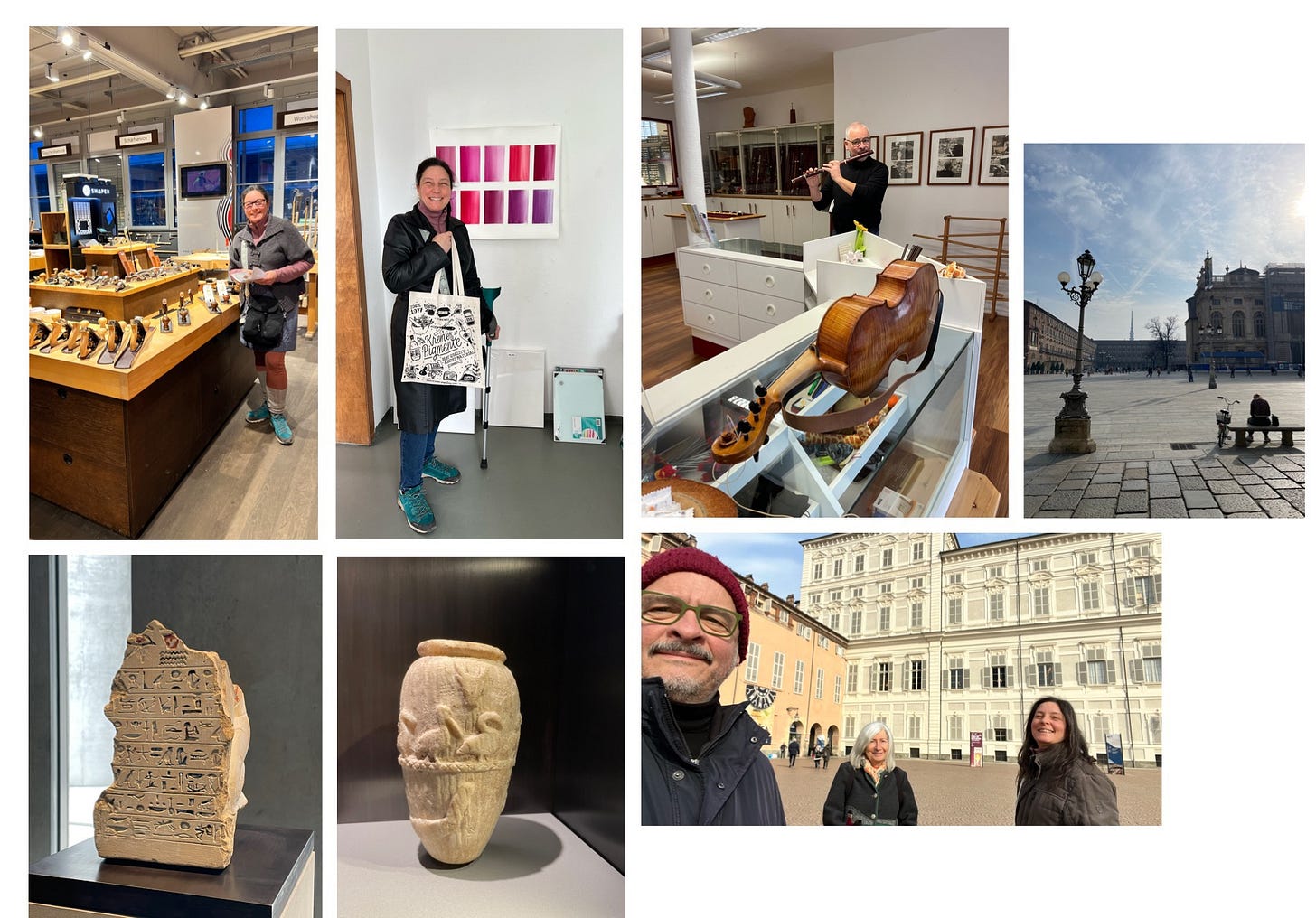

We had a lovely week off, not a fancy holiday, but we felt we were on a nice and much-needed break. We first went to Munich (where we enjoyed a visit to Dictum and Kremer, two shops well known to luthiers: tools and pigments! - we also visited the Egyptian art museum, really worth it even if you are not super into Egyptian history) and Singen in Baden-Württemberg (where we ordered a new transverse flute for Alessandro). Then we visited Daniela’s mother and we attended a karate training session in Turin. It was around 2600 km drive in one week, but we are now recharged and back at work!

Both of us are working on the top of our instruments, watch the video to see how beautiful they’re coming out!

Featured video of the week

The magic of two Spallas on stage!