Last week we attended a seminar on violoncello piccolo. Unfortunately, we had to leave before the round table because our dog sitter had strict timing. We heard the presentations of Mark Vanscheeuwijck and Kai Thomas Roth, they were highly informative and entertaining as well.

A complete review is impossible here, but the topic was so important to us and to all the Violoncello da Spalla players that I will try to go deeper into our future issues.

By now, I would like to address a question that popped up recently on Facebook: which is the repertoire specifically written for five strings cello?

First, we should clarify what a five strings cello is. It is not as obvious as it may seem. It should be distinguished between the big and the small five strings cello. The big one is an instrument played in Italy in the early baroque, when cellists hadn’t yet developed the thumb-capo technique, and so they needed the fifth string to reach the highest notes of their repertoire. Then, following M. Vanscheeuwijck, at the beginning of the 18th century, in Italy, the violoncello was standardised on his “modern” big size, four strings, vertical playing position, and upper hand grip. The big five strings violoncello was never part of the continuo group but played in the ripieno group or as an obbligato instrument.

Then we move to Saxony and surrounding regions, in J. S. Bach’s time and area, and we have this small cello, played either on the shoulder, horizontally, or vertically on the knees, much smaller than the previous “Italian” one, which could have four on five strings (when it had four, it was tuned GDAE.)

And, according to M. Vanscheeuwijck, only from the beginning of the stile galante do we see the cello as a part of the continuo group.

This means (I add) that the small five strings da Spalla was part of a continuo group on top of being an obbligato instrument.

(How about Mattheson? But as I said, I will get back to all this later).

So, back to our list of repertoire written specifically for five strings cello:

J. S. Bach, 6th suite: (M. V. questions:) could the fact that the tuning is so specifically indicated mean that it was unusual? This is the only piece of repertoire we know we are sure is for a five strings cello. Most probably a big one, not the violoncello piccolo used in the cantatas, as Bach himself specifies “a cinque cordes” in the suite, “violoncello piccolo” in the cantatas.

The violoncello piccolo or viola pomposa has a very strict specific repertoire, which may refer to four (tuned GDAE) or five strings: Telemann, Graun, Herrando and Lidarti. And, of course, Bach’s cantatas. (According to M. Vanscheeuwijck these pieces may be written for a five strings violin, or something tuned like a viola, but he also says that when the violin clef is used, it is octavised, played one octave below. I would add that an instrument considerably bigger than the violin cannot be tuned like a violin, with the same E at the same pitch.)

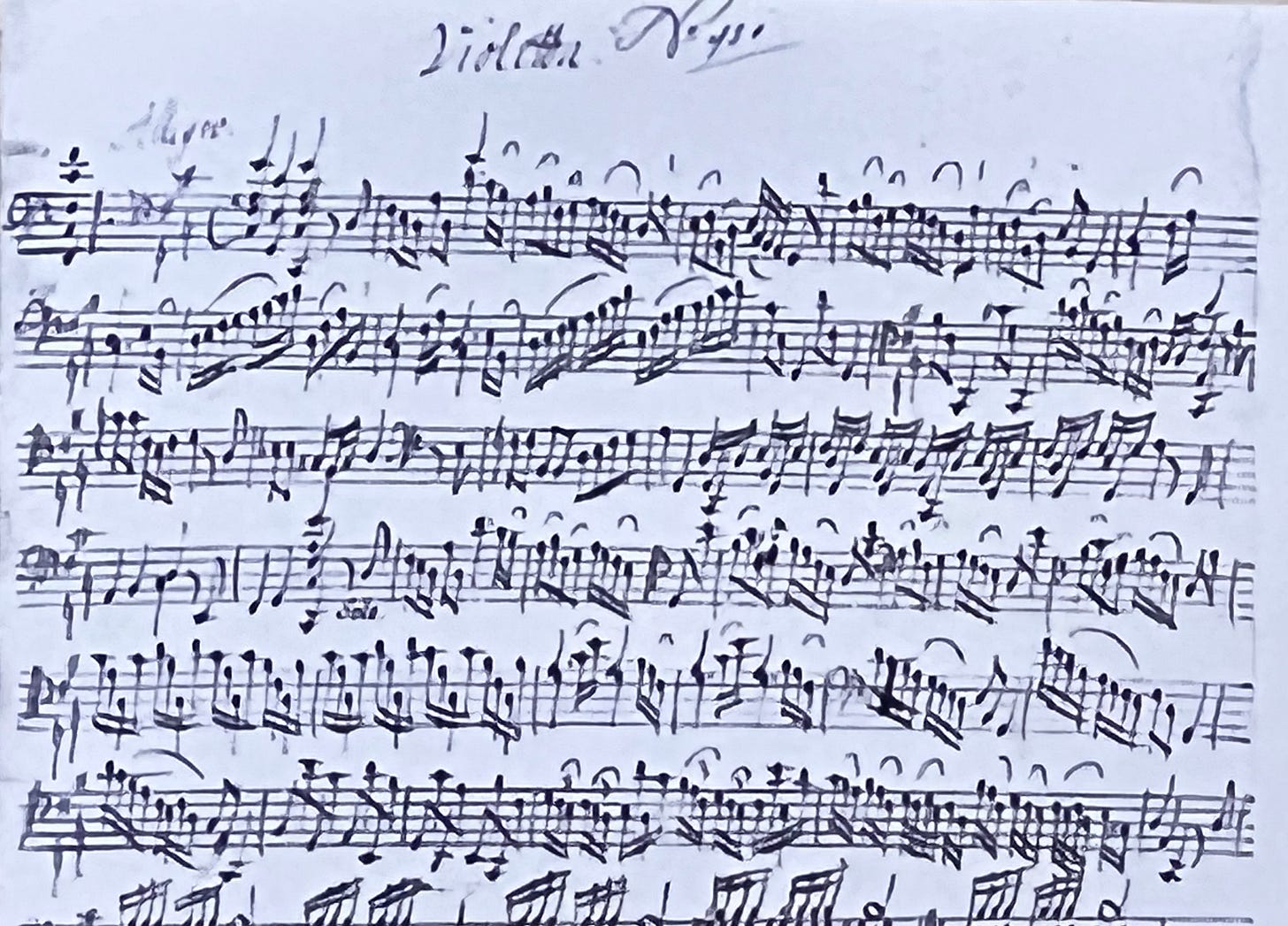

The terms violotto, viola, violetta were used by Antonio Vandini, Emmanuele Nappi, Evaristo Felice Dall’abaco, Tartini (viola, concertos written for Vandini), Johann Martin Dömming. They may have all referred to a violoncello piccolo with four (GDAE) or five strings.

Giovanni Battista Sammartini, concerto in Do maggiore per violoncello piccolo o violino (JC69)

Mark Vanscheeuwijck concludes that the five-string cello (the big one) was an option for the 17th-century bass or bassetto part that goes in a higher register, as well as for simple early 18th-century sonatas, a few concertos and some compositions by Graun, Abel, C. P. E. Bach, Reichenauer, Policarpo, Dömming, Tartini…

He recommends avoiding (for us Spalla players) Neapolitan repertoire because that was the cradle of the “modern” standard cello. In Supriani’s time, the left-hand thumb technique was already in use, and the five-string cello was abandoned. He would like to restrict us to the viola pomposa repertoire, but… there is still that vast Italian baroque repertoire, for violoncello, violoncino or whatsoever, that is so suitable and comfortable when played with a five strings cello da Spalla. And was originally played with small cellos with four strings GDAE, or maybe with five strings.

I know that what I am to write here would not be accepted in a research environment, but of all the baroque cello repertoire (including bass, viola, violetta, violotto, viola da spalla…), I would say that everything that sounds well on the Spalla, is to be freely and confidently played on a Spalla without being afraid of being out of place. I am sure they would have done so.

To the talk of Kai Thomas Roth, I owe something entirely new to me, both in organology and repertoire research. In England, during the second half of the 18th century, an instrument called the “pentachord” was in use. From Wikipedia:

The name "pentachord" was also given to a musical instrument, now in disuse, built to the specifications of Sir Edward Walpole. It was demonstrated by Karl Friedrich Abel at his first public concert in London, on 5 April 1759, when it was described as "newly invented" (Knape, Charters, and McVeigh 2001). In the dedication to Walpole of his cello sonatas op. 3, the cellist/composer James Cervetto praised the pentachord, declaring: "I know not a more fit Instrument to Accompany the Voice" (Charters 1973, 1224). Performances on the instrument are documented as late as 1783, after which it seems to have fallen out of use. It appears to have been similar to a five-string violoncello (McLamore 2004, 84).

This happened when Johan Christian Bach, the younger of J. S. Bach’s son, was enjoying a career in London and frequently performed with Abel.

Definitely, late 18th century London is a good source of five strings cello music, keeping in mind that the pentachord was bigger than our Violoncello da Spalla, played between legs, and with a vibrating length of around 60 cm.

Another place and period to research music is 18th century France, the France of the makers Guersan and Castagneri, who made several small cellos, some with five strings.

The same France of the composer Pierre Guignon.

Born in Turin [Like me! And like Castagneri], Giovanni Pietro Ghignone (10 February 1702 – 30 January 1774) was the son of a merchant from this city and a disciple of Giovanni Battista Somis. He gave his first performance in Paris in 1725. He became a musician in the chapel of the Prince of Savoie-Carignan in 1730, a position he retained for about 20 years. At the same time, he was admired by the queen and also entered the royal chapel in 1733, where he remained until his pension in 1762.

His merits as a violinist earned him the nickname of "Roy des violonistes", i.e. director of the ménestrandise, a title which was then in disuse and which would be deleted after him. The performances of his own concertos and those of the Venetian master Antonio Vivaldi at the Concert Spirituel were received with great success.

A viola da gamba piece and a solo harpsichord piece by Antoine Forqueray bears his name: La Guignon, published in 1747 by Forqueray's son Jean-Baptiste. However, the similarity of age between Guignon and Jean-Baptiste may indicate that Jean-Baptiste actually wrote the pieces, and published them in his father's name.

In 1741, king Louis XV granted him French nationality and the title of "Royal Master of the Menetriers". Guignon thus supervised the singers and dancers of the kingdom, officially becoming the first violin of the time.

Guignon died in Versailles aged 71.

(From Wikipedia)

Enjoy this video by the Fernandez and go on their YouTube channel for several other videos featuring their Violoncello da Spalla

If this post is of some help to find something good for Violoncello da Spalla repertoire, if you fall in love with something mentioned above or if you find something new that you love playing on your Spalla, please let us know!

Summer-break announcement:

I decided to take a break for the month of August. I may post some more news from us to keep in touch, but not articles. I am preparing new content for the autumn. As we have a few trips planned, publishing every week could easily become stressful, risking to provide you with arid posts. None of us wants to loose time, so I wish you all the best for the end of the summer (if you are on the north hemisphere), and I’d like to suggest you some

Further readings:

http://www.geraldfinzi.org/uploads/8/5/7/5/8575857/2012_jennifermorsches.pdf

https://www.jstor.org/stable/40731346

Updates from our workshop

Alessandro’s viola has the back glued in place, and also my Violoncello da Spalla is getting on well. We are now at my parents’ place, but we’ll be soon back in the workshop!

Last weekend we received the visit of Daniel Bayle, from Toulouse, who plays and makes Violoncello da Spalla. We had fun playing together and exchanging making experiences and tools suggestions. For me it was a new and exciting experience to play with another spalla as in a section (we played some music where there were unisone phrases). It was powerful!

My personal plan for this summer is to practice with Alessandro the flute sonata by J. S. Bach BWV 1034. The bass part is very active, constantly engaged dieting with the flute. The third movement is so beautiful that moves me to tears each time!