The Italian legacy of harmonic proportions design

Uhm... What’s behind such a pompous statement? It’s just very basic musical theory, applied to tangible things!

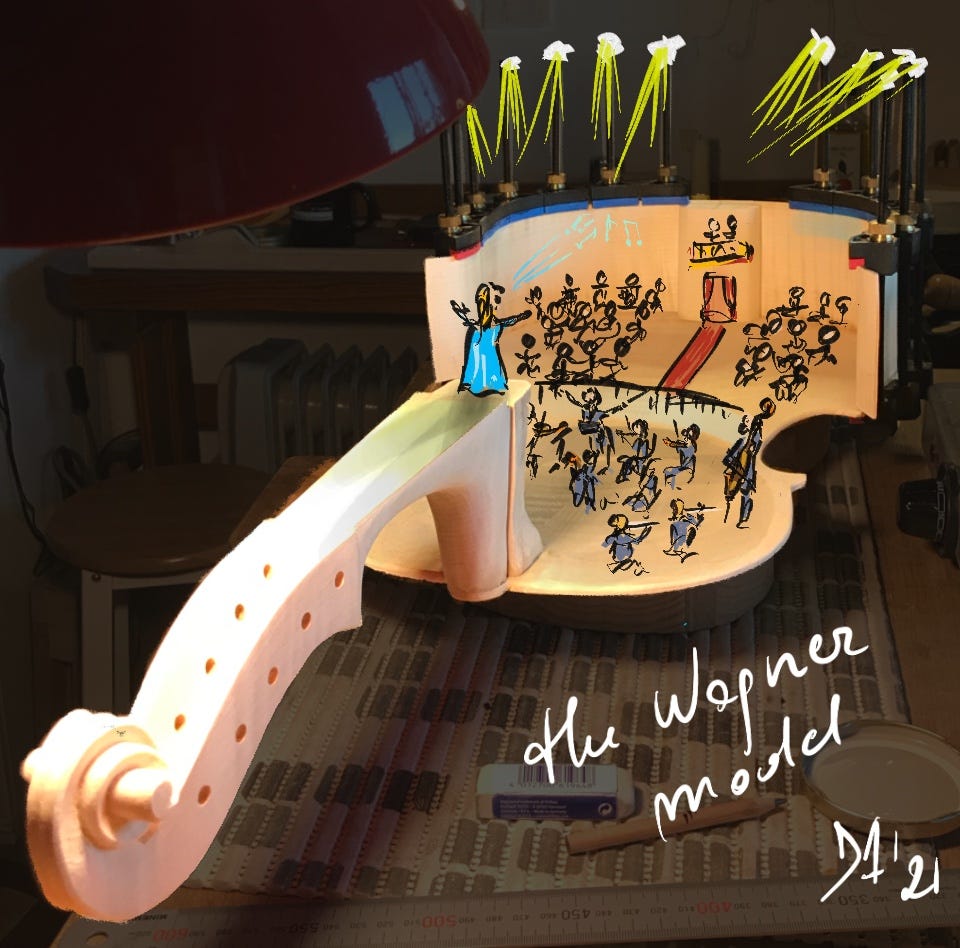

From 1997 to 2015, I was a viola player in the Olympic Theatre in Vicenza.

Entering that stage is something extraordinary that unfortunately cannot be imagined by the tourists visiting the building or by the audience. At first, it requires good balance (and not too high heels) because you are walking inside of a trompe l’oeil perspective scenery, so, basically, the inclination of the floor of the entrance corridor is something like 25 degrees, and this left to right, this adding to the usual down way to the stage. When you get in, the scenery is spectacular: you are in an ancient square with a blue sky, and the audience is sitting on (rather uncomfortable) big round steps, so you see every single face. And when you start playing: well, it’s so crispy clear that it’s almost frightening. You can hear everything, but it is so different from any room or open-air experience you had. And this is because this theatre was made not for big orchestras and grand coda pianos but for staging Greek and Roman tragedies, which also included some music. So no redundancy at all. Every single whisper from the stage is heard clearly from the last person on the theatre's highest step. You can experience this in every surviving Roman or Greek theatre.

The Accademia Olimpica in Vicenza, one of those group of nobles and scholars studying ancient culture that shaped the Italian Renaissance era, commissioned the Olympic Theatre to the famous architect Andrea Palladio. It was to be included in a pre-existing medieval complex and was to be a Roman/Greek theatre, but covered. It is the oldest surviving today of this kind.

The Olimpic Theatre was built between 1580 and 1584, and the opening night saw staged the Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, with choruses’ music by Andrea Gabrieli. The original scenes for that occasion, representing the streets of Thebe, are what artists still walk in today.

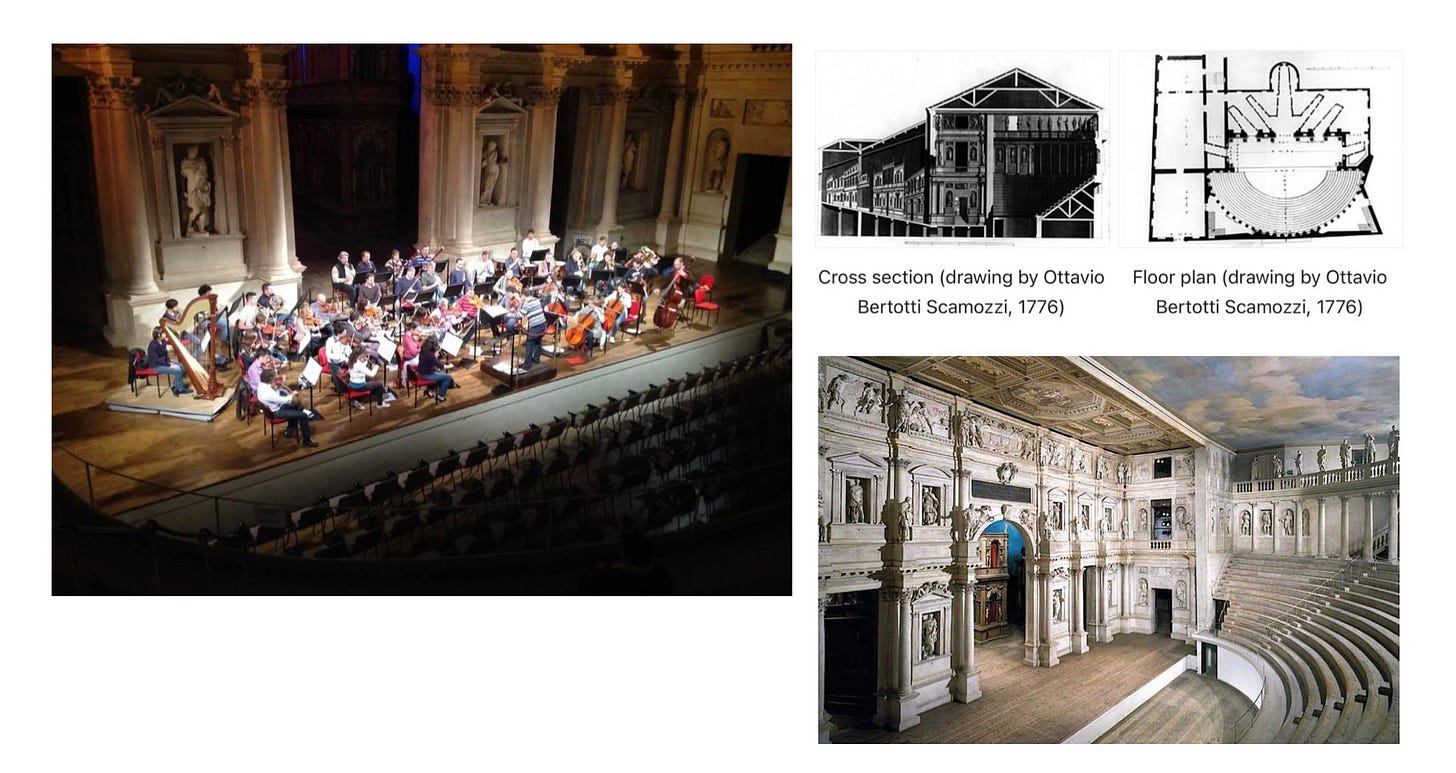

Andrea Palladio is one of the most famous architects of renaissance Italy, copied abroad for centuries, from the Palladian villas in Kent to the White House in Washington. For three years, he studied in Venice with Gioseffo Zarlino, music theorist and composer, and mathematician, astrologist, theologist. This news shouldn’t surprise us: Music is the bridge that allowed them to translate math speculation into reality. Actually, speculation was not a concept at all at those times, as math, philosophy, theology were all the approaches required to study nature: the world nature, human nature, divine nature. And Music was the code that permitted a translation between them. So, for an architect, music was as important as a field of study as math.

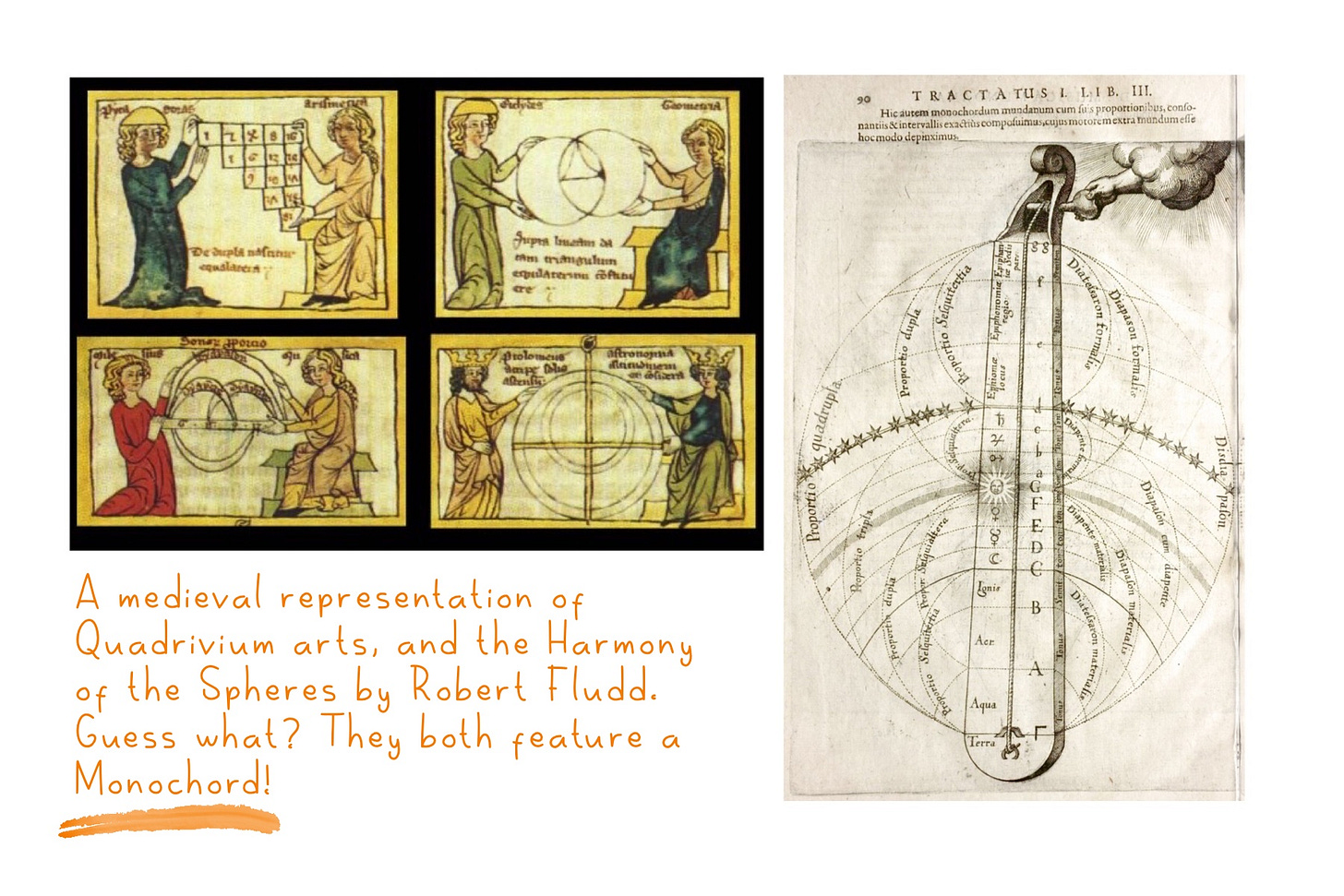

Zarlino’s efforts were all into trying to obtain on earth the perfect harmony of the spheres. Pitagora discovered using a monochord how some notes (octave, fourth and fifth) were perfectly corresponding to mathematical proportions (1:2, 2:3, 3:4). But the other notes used in music were obtained by applying these same proportions to the resulting notes (the second is 2:3 on the fifth, as an example), with the consequence that this “round of fifths” didn’t close perfectly on the octave. Some adjustments were needed to allow instruments tuned by ears from musicians, who applied this fifths principle, to play with fixed tuning instruments like big church organs. This is how temperaments came into play. Zarlino tried hard to establish some sort of order in this tuning problem and was the first to recognise the importance of the third, major or minor, to establish the key of a piece, in other words, to settle a code into a composition. Zarlino, to simplify things, is often mentioned as the father of harmony.

Can you see how Harmony, as a superimposition of notes and “mathematical proportions” is Architecture? And why Palladio searched by Zarlino for his solid knowledge as a prominent architecture?

What we have to keep in mind is that the instrument to investigate the universe was not a computer but a monochord. The substantial harmonic proportions were found by Pitagora on a monochord, by hearing music, by hearing consonant notes. For Pitagora music and math were not two distinct things, but right the same thing, one (music) the practical application of the other (math), or better say music was the tool to investigate math (and, the universe).

Harmonic proportions mean precisely this: musical proportions, not pure math.

One other student of Zarlino was Vincenzo Galilei, lutist, father of Galileo and one of the founder of Accademia dei Bardi in Florence, where the music historians usually collocate the birth of Opera, between those who were trying to revival Ancient Greek tragedy and its music. If we think at music as the gift we were given to understand nature and word as the gift God sent us to communicate and express our feelings, it is pretty clear why these two fields of study, quadrivium (math, geometry, astronomy, music) and trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric), were the basics before one had access to study theology and philosophy. And at the same time should be obvious why Greek tragedy, and Opera, are the two highest form of arts.

In Florence, in the same entourage of Vincenzo Galilei, Giulio Caccini and Jacopo Peri, there was another famous Italian Renaissance architect: Leon Battista Alberti. In the notes for the building of the Rucellai Sepulchre, he wrote that the decorations on the upper part must be kept at musical intervals. Which, in modern language, is translated as harmonious. But today, we have lost the connection between “harmonious” as harmonic and musical, meaning harmonious just “well proportioned”. We don’t get that those proportions were intended as musical proportions, not mathematical proportions.

Going practical. What is this monochord, and how could this help in designing a palace (or a violin)?

It is very simple: take a string long as your unit of measurement. In the case of a violin, we take as a unit the string length, of course. In the case of a building, it could be the door, the length of the square it has to face, or other relevant elements. Then, find on this same string, on the monochord, the other notes of the scale: pure fourth and fifth, and, more interestingly, all the other intervals. With an intonation that you like, that sounds good to your feeling... and temperament 😉. Then we use to design your violin (or palace) only lengths corresponding to these intervals. This way, we make sure that the design is harmonic and the building or instrument will have a great acoustic.

What’s that big deal in designing a violin with a monochord? Why should one bother to do so? Isn’t it enough, if not better, to copy a Strad from a poster?

To me, it’s inspiring seeing that Italians made great use of thirds, sixths and even seconds and sevenths, while, for example, Germans made wide use of fifths and fourths. It is exciting the idea that you can give a character to the instrument by applying a temperament. Most of all, it is exciting knowing that each measure had a meaning, a musical meaning. And, it could be passed to one’s apprentice by teaching a melody. It’s not numbers, it’s music!

A poster has massive lens distortions, and it is not reliable at all for measures! Check any poster with the measures of the same instrument, and they won’t match! And about doing a bench copy, copying from an important instrument that you have in your hands, on your bench, this is an excellent exercise to understand better an author, his tools, his making process... and it is way more interesting if everything is checked with harmonic proportions, not as mere speculation but to be able to replicate something, maybe at a different scale, like making a smaller viola from a tenor, or a smaller violin for someone with tiny hands... or, a violoncello piccolo from a bigger one.

If, for instance, you ask us to have a shorter neck, shorter corners, or longer ff holes, all this is not made by guessing nor even by a calculator, but by studying the old instruments, the proportions they used, and through the monochord applying them to the instrument we are to make.

What adds to this excitement is knowing that, before Strad, when they didn’t have Strad to copy 😛, this is how they did. If you think a moment, it is so simple, it reduces the tools you need, you use musical ears instead of making math, you just need to open the compass at an interval found on a monochord.

There are treatises explaining musical instrument proportions (Pablo Nasarre, 1723), and others stating that a building should be designed like a musical instrument, using musical intervals (Leon Battista Alberti). Then, after Strad, violin-makers (and architects) forgot this knowledge. They started making copies!

I love when I find a way to make things more simply and in a way it could be feasible in the past. And what’s more natural than using music to design a musical tool?

News from da Spalla world

Tomorrow night, 22nd of May at 20 European central time, a streaming concert by the Väsen Duo, with Mikael Marin at the Cello da Spalla and Olov Johansson at the nickelharpa. Stories and folk tunes for a night in front of the fireplace (or on the porch if you are in a warm place)!

Updates from our workshop

I’m back at home now, so I have more to share! The new violoncello da spalla is taking shape, almost looking like a real cello!! Ops... 🤭 I really enjoyed doing the belly joint with our new bench plane, using a fabulous spruce from Latemar mountain, hand split with wedges by Luca Pozza. Luca is a violist in the orchestra of Arena di Verona, I know him since I played there in 2005: he was my stand mate at my fist night. He also did a bit of violin making before starting a tonewood business, so I totally rely on him for quality resonance spruce!

Alessandro’s violin is getting closer to its final color.

Featured video of the week

Relax and enjoy this Vivaldi Concerto by the great and only Sigiswald Kuijken!