Sources that mess it up

Treatises that mention Violoncello da Spalla, but we’d prefer to hide them under the carpet

Let’s admit it: we research in the hope to find a source telling us precisely what we are looking for. What a dream to find a treatise or even better a tutorial book that explains how the violoncello is played resting it on the chest, with the help of a strap, and how the left hand is pushing a bit forward so that the body of the instrument is firm towards the right shoulder and doesn’t slip in changes of position.

Instead, often we find an authoritative voice messing everything up. It reminds me of those grannies that stop you outside of the concerts to tell you how beautiful was the sound of your big violin… not to mention that close relative who asked why did I want a violin bigger and bigger, which was lower and slower… 🙄

Don’t we hide the head below the sand, let’s face them straight. Here is a list of what I have found that I wish was more clear. Add yours in the comments (I am sure there are others that my head keeps hidden in the attempt of protecting me!) Or simply comment if you find they are meaningful!

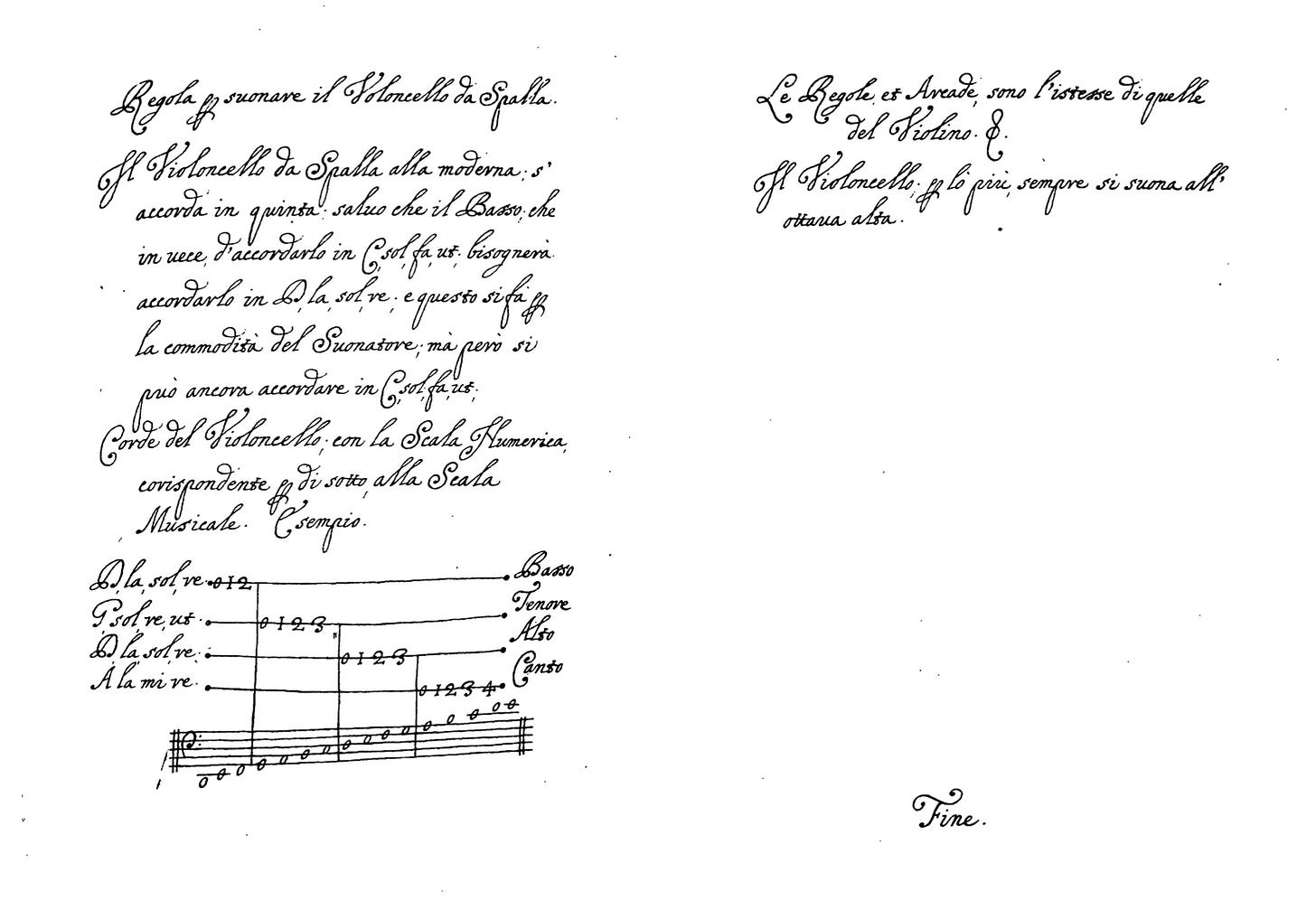

Bartolomeo Bismantova, “Compendium Musicale”, in the second edition of 1694 in Ferrara, adds a folio with his rules to play doublebass, Violoncello da Spalla, and Oboe. His treatise mainly talks about recorder, cornetto, and harpsicord. Let’s note that in the first edition, 1677, those new instruments were not cited, while in a way they seemed indispensable in 1694.

“How to play the Violoncello da Spalla: the Violoncello da Spalla in modern fashion is tuned in fifths, except for the bass, that instead of being tuned in C, you would tune it in D, to be comfortable playing. But you can also tune it in C.” The example mentions the strings and the scale, in which the numbers are not fingerings but only the grades of the scale on that string. “The way to play it and the bowings are the same of the violin. The Violoncello da Spalla is almost always played at the upper octave”

So, Bismantova is noticeable because he coins the therm Violoncello da Spalla, but at the end, we seem to end up with a viola, which has the lower string tuned one tone higher, and it reads in bass F key. Which seems quite unnatural: as tenor voices were already reading in violin G key singing one octave lower, why a “tenor” instrument should read in bass key and play one octave higher? Ouch…

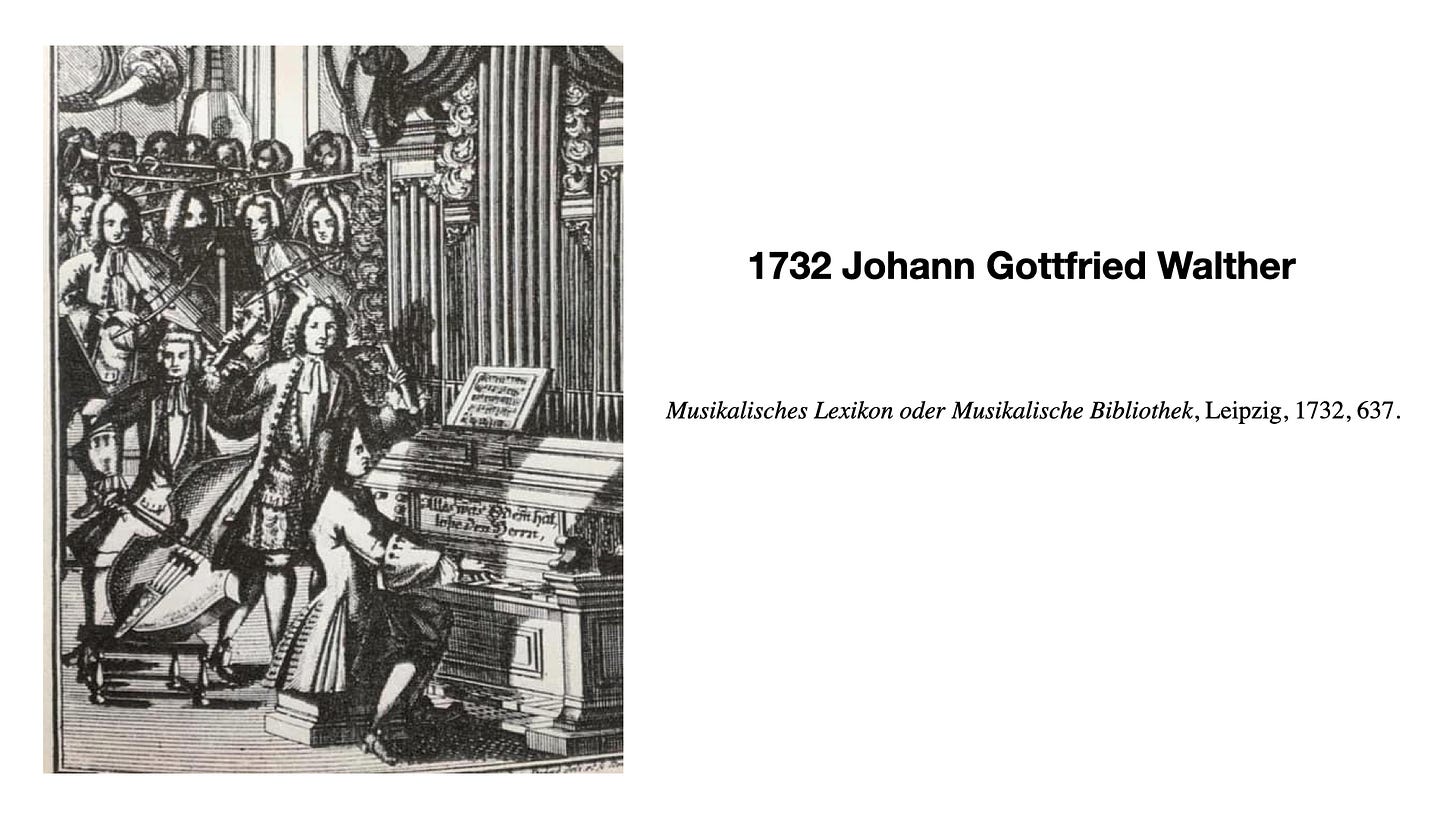

Johann Gottfried Walther, “Praecepta de musicalischen composition”, Weimar 1708.

“The violoncello is an Italian bass instrument, not different from the gamba viol. It is played almost like a violin, as it is supported with the left hand, which does the fingerings. Partly however, due to its weight, is hanged on a button of the mantle, and it is played with a bow in the right hand. It is tuned like a viola”.

Uhu… no comments needed here from my side I guess

Johann Philip Eisel, Musicus Autodidacticus, Augsburg 1738:

“About Violoncello, viola bassa or viola di spalla. We want to put all of them into the same soup: because all three are small violin basses on which you can realize with less fatigue compared to the bigger violoni, fast things, mannerisms, variations, and so on.”

So are we here in front of three different instruments?

Do you know other treatises who seem to mess it up? Or do you have better translation (or you can read the originals) in a way that they are more meaningful? Comment below, any comment can bring a valuable discussion!

Updates from our workshop

For me it was a week of shaping blocks of the Violoncello da Spalla and bow rehairing, so not much to share… Alessandro is almost finished with his scroll.

It’s October! My favourite pastry month, because it is the month of chestnuts! In South Tyrol there is a variety of desserts made with chestnuts, and it is hard to make a choice! This week we had ice cream, chestnut cake (cakes here always contain lot of cream!), and Kastanienherzen, literally hearts of chestnut. A heart of the thinnest dark chocolate is filled with chestnut purée and topped with cream…

Featured video of the week

J. S. Bach godfathered Hoffmann’s sons, and Hoffmann godfathered C. P. E. Bach’s son. So close was the relationship of the two families. We also know that C. P. E. had at home a cello piccolo by Hoffmann, maybe the Berkeley’s one? We’ll never know. But we like to think that C. P. E. tried on the violoncello da spalla the bass parts of his sonatas, and this sonata is a true masterpiece.

This is a video we made during the first lockdown, when we did our first attempt to play together! The cello is Alessandro’s first one.