This issue will not follow the usual format, as this week got so far from any usual format that I feel the urgency to share all the news at once. I cannot keep them for three separate issues!

You already got the plan in the title, so let’s go straight to it!

What to play on Violoncello da Spalla: Giovanni Battista degli Antonii

Giovanni Battista degli Antonii (1636 - 1698) published in Bologna in 1687 “Recercate sopra il violoncello o clavicembalo” (Recercate for the violoncello or harpsichord), op.1

G. B. degli Antonii received his musical education from his father, organist and composer, and took at an early age the place of his father as trombone player in the Concerto Palatino, the wind group in Bologna which was so often opponent to the Cappella di San Petronio (which was mainly voices with a strings group) for the privileges of playing at important ceremonies. He was also component of the Cappella di San Petronio for a short time, until being dismissed from Cazzati who wanted a different ensemble, and he tried many times to be admitted again as organ player. He was also a member of the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. He was, in other words, right in the centre and in the period in which the Violoncello appeared on the scenes.

We find in Mark Vanscheeuwijck:

The twelve Ricercate sopra il violoncello o clavicembalo by Bolognese organist and trombonist Giovanni Battista Degli Antonii (166-1698), printed in 1687, have been considered to be the earliest compositions ever published for solo cello. We now know that the printed violin part was lost and that the Biblioteca Estense possesses a manuscript with the Ricercate per il violino, which is the violin part to these duets. Both part-books have been newly published in 007, and cellists should no longer think of these pieces as solo compositions. It is astonishing that in the Ricercata Ottava, the range of the cello part is C-c”, a third or fourth higher than any other late 17th-century composition for bass violin, which could indicate that a five-string instrument might have been intended.

But also, same from him, in a previous work:

Degl'Antonii, I believe, was really thinking about a violoncello da spalla with five strings.

You can find the original manuscript of the cello Recercate for free here:

and a more convenient transcription in modern print here, which I highly recommend for its accuracy:

You can buy a downloadable pdf of the separate parts (the cello and the violin one) and choose between the printed version of the score or the downloadable pdf.

I bought with enthusiasm the violin part thinking about playing it with my flautist husband, but after the first reading, we dismissed the idea. I totally agree with the publisher Alessandro Bares who writes in his notes:

[on the original print cover] ...words “o clavicembalo” are written much smaller than “sopra il violoncello”, just to tell us that the first destination of this music is violoncello. The peculiar style of these pieces for solo cello, and some bass figurings (obviously intended for performances with a harpsichord), made some musicians think that this music wasn’t written for solo cello: you easily recognise some beginnings of themes (in the style of polyphonic ricercari or fugues) alternated with passages in the basso continuo style.

It seemed evident that a part for another instrument (presumably a violin) was lost.

And the “lost” part was found in a manuscript [...]

Unfortunately, enthusiasm for this “discovery” ended as soon as the “reconstructed” version was examined or performed: if the version for solo cello can leave us a bit perplexed, the version with violin is completely senseless. (In musicology, you cannot say “ugly”, but this is precisely what I wanted to say). The violin part has nothing to do with what you expect from a violin part written by a member of the Emilian school (Corelli, Vitali, Bononcini, etc.): it is nothing more than a pedantic exercise in counterpoint, written by an unknown musician who tried to “complete” in a very clumsy way pieces which were not at all basso continuo parts, and didn’t need to be completed. The end of the XVII century was the golden age of Emilian school, and violin parts were characterised by marvellous melodic cantabile and vivacity. Both are completely missing in this violin part.

[...] I think that the version with two instruments has nothing to do with G. B. Degli Antonii. Still, I wanted to publish it to divulge it and help decreasing rumours about the rediscovered violin part.

As I said, I couldn’t agree more with A. Bares here, and I was almost shocked by the nearly continuous homorhythmic character of the violin part with the cello. Where I expected a fugato or a hint of a dialogue, nothing. So frustrating! This completely put me down on my idea to record this works with the two parts. But I still find some of these recercate very pleasant for our little Violoncello da Spalla, and I highly recommend them if you are interested in playing original music for this instrument.

Single wound basses: a slightly provocative string to ignite a tiny revolution

From Mark Vanscheeuwijck, we read: “in order to make such tiny instruments work at 8-foot pitch, a double-wound string is indispensable – but it is not documented before the mid- 1760s.” You can find my detailed answer to this in my previous article here.

However, there is something significant that happened just this week and needs to be considered here:

I am in a WhatsApp group with Eliakim Boussoir and other string makers or strings enthusiasts, and we were discussing double wound strings, those strings in which you need some extra weight, so you wound them twice, that is to say, in two layers of wire. This way, you obtain a tiny core that carries a lot of metal weight. The sound usually is easy but a bit loud and metallic, sometimes close to nasal. Even if I appreciate the easy response, they always seemed lacking some substance, some fundamental deep earthly character which I like in basses. But I always accepted as evidence that the violoncello da Spalla, being an extra shortened instrument, needed this kind of strings to work properly.

I started to investigate the possibility of single wound basses on request of Koji Otsuki, as his research attested that Bach seldom used basses, so maybe he didn’t have those double wound. But I was still convinced that he probably had them since Leipzig was at the centre of technology evolution at that time, and considering also that the G if the spalla is already not the fastest response string in the world!

So, when Eliakim wrote that he was convinced he could make those single wound basses, I didn’t pay much attention. And when he proposed them to me, since I have little time to prepare a presentation for next week, I suggested that Koji would probably appreciate them better than me. But he sent them out anyway. At this point, I couldn’t ignore them!!

Still, I didn’t expect them to be so easy and convincing! He managed to make a super flexible gut core, so the C single wound big bass speaks fast, with no extra effort compared to any other gut core string.

I find this a milestone in the acceptance of the historical reality of the small violoncello da Spalla. This is why I put all my efforts this week into making this video.

Please don’t just judge my playing or my Degli Antonii interpretation, but think at what you could do with an instrument like this, how your basso continuo would sound, and how it could sound in Bach’s obbligato parts... would it be so indecent?

Two other things to consider is that this Wagner model is exceptionally short, 40 cm scale, and that this C string is a prototype wound with copper, lighter and bigger gauge than silver, so it would be much better when wound with silver!

You can order these strings here.

The Johann Wagner’s voice, finally!

Well, to be honest, the voice of MY Johann Wagner, which I did my best to make as close as possible to the original, not to make a perfect copy in aesthetic, but paying attention to be close to the measures and the way of making it. I also, of course, checked its harmonical proportions, and I loved to find them everywhere. It was made with knowledge.

I will say more about its construction in the next issue, as this one is rather long and intense. In the meantime, you can enjoy pictures of the making in the video above.

While making it, I tried to imagine the result: how would I’d better tune it, would it be capable of playing, so short, with the standard double wound strings we use for the Badiarov? 🤦♀️I expected a nasal sound, maybe beautiful trebles but not so exciting basses. I was amazed when I heard its voice. It has deep basses, it is very even in the passages from one string to the closest one, and its trebles are those of a brilliant tenor. He is not a nobleman but a joyful peasant, and I enjoy a lot playing it! With such a short neck, it’s hard going over the third position, but its range is wide enough and full of harmonics. I don’t miss high positions at all. Its repertoire is vast anyway, even without the sixth suite, and especially if you consider him as a portable bass for continuo, a proper dance instrument. An instrument meant to enjoy life and music.

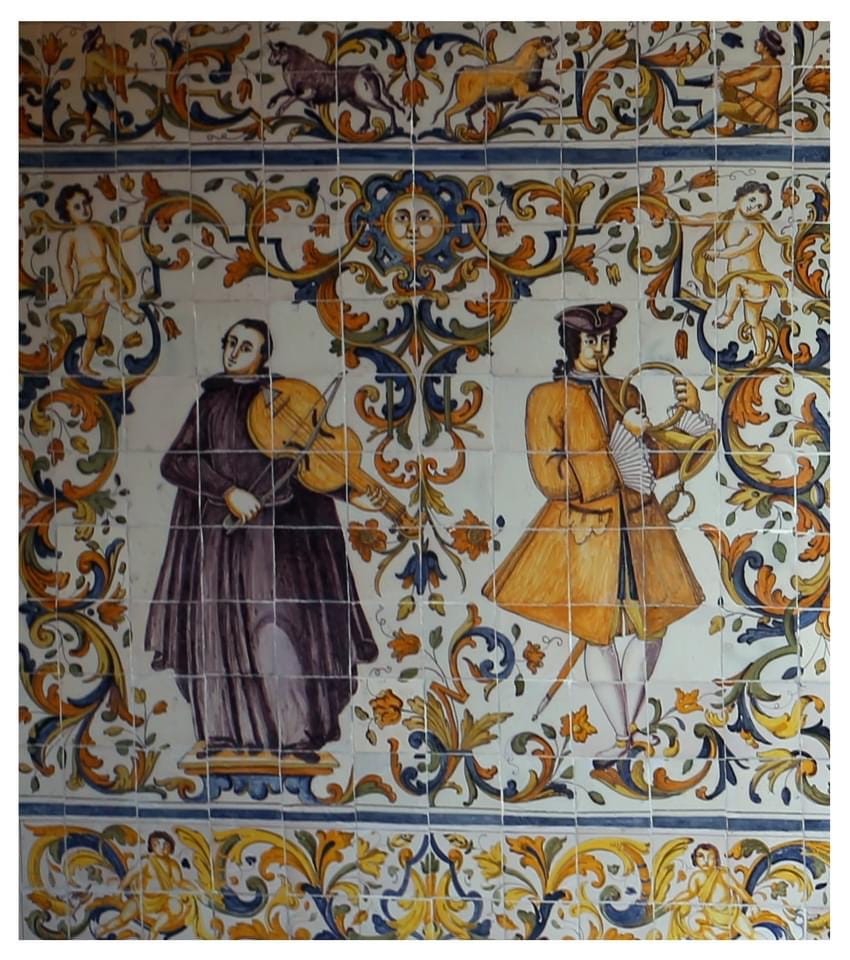

The week of da Spalla everyday life iconography

Another thing that happened this week is that everybody started sharing on Facebook iconography with exceptionally small cellos, or exceptionally big violas, or cellos da Spalla. But these images were different from the “usual” ones because they were not settled in an epic, elegant or sacred context, but in everyday life. Sometimes even rather funny, but without a doubt, everyday life.

I used them to decorate this article, thankful to those who shared them. They were all new to me!

Unfortunately, it is rarely the case that you can get the source in those posts, so I don’t know where they are from, and I would appreciate and be grateful for more precise pieces of information in the comments below, please!

I want to end here with my cartoon on how my week was. Thanks for reading through!

Dear Daniela,

thanks for your exciting article, I will ask Eliakim Boussoir for the new single wound basses. I’m looking for the nice combination with gut strings, because I need it for some concerts in September. The Aquila strings are to weak for my instrument (vibration length 41cm) by the pitch 415Hz. So I tried to get more tension with another bridge-position - now it it 42,7cm -, it works well. If, but, I can get the better condition with this single wound basses, it is possible to play with shorter vibration length. It will be more comfortable for my left hand...

I want to write you here about Antonii’s ricercatas. Is it the notation for the „partimenti“ ? You can find nice article by Wiki about partimenti (english version is better than another language) - one method for the improvisation with bassline as help-material. This facsimile seems one typical notation for partimenti, you (or your husband) can improve freely with this cello part, also with counterpoint. It is very interesting - you find some „motives“ by Antonii-Recercatas what you can find by Corelli (for instance, Concerti Grossi op.6).

This is just my guess, maybe the musicologists have other explanation...

I will try to make melodies for this recercatas, maybe :-)

best regards,

Chiharu