On dragons, beasts, and other cellist creatures

…or about the Violoncello da spalla Arcangioli in the Leipzig Grassi Museum

It’s a mundane fact that museums’ storage hosts unusually shaped instruments, often classified as oddities or experiments and not shown in the exhibition. In Leipzig’s Grassi Museum, on the contrary, the exhibition features many unusual instruments, all of them of a high level of craftsmanship if not widely recognised as masterpieces.

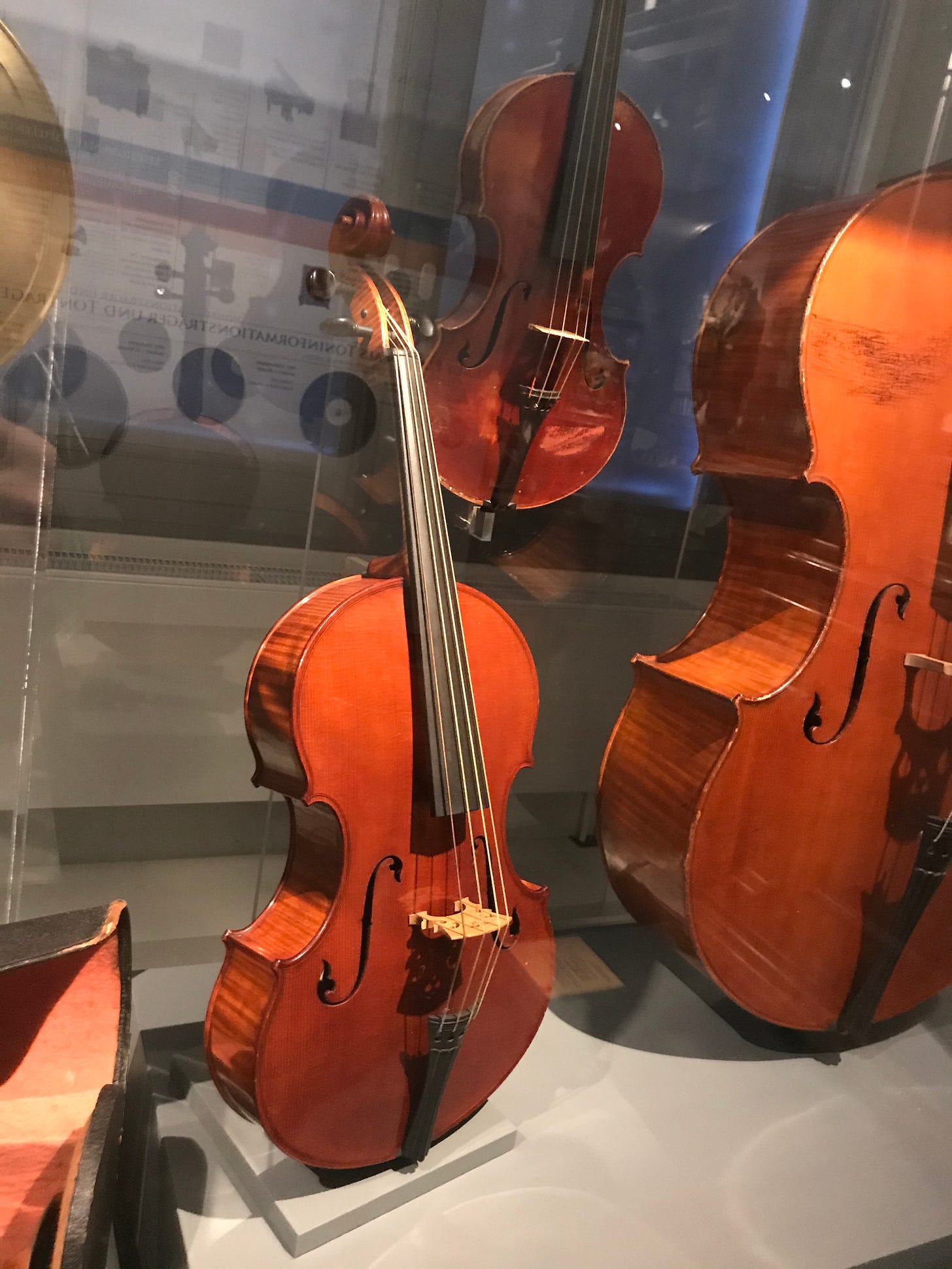

And… a Violoncello da Spalla, by Lorenzo Arcangioli, Florence 1825. This is one of the very few, if not the only one, to be catalogued in a museum list with this exact name. The curator Veit Heller is proud of this piece, while it seems that luthiers or researchers do not pay great attention to it. In fact, at first sight, it looks fallen out from a Gaudì painting, and still, your brain tries to put it into the jazz instruments section… and finally, you give up and read the label. And you discover it is from one century earlier than what you expected. And from Italy. And from a time in which you were thought that the classical quartet was perfectly standardised, especially in Italy. So you stay there, with these two voices whispering in your head: “fake, fake, fake”… and the other “but why, why, why?” …and you start to contemplate.

I didn’t have the opportunity to try to play it (so far). However, from my little experience of violoncello da Spalla playing this instrument has two noticeable features that come as a confirmation of 1. The posture 2. The attempt for virtuoso repertoires.

The second is simple: precisely like a modern guitar, it has a cutaway shoulder to make the highest positions more comfortable. This implies a repertoire and performing strings. And, of course, the demand for a more performing cello da Spalla.

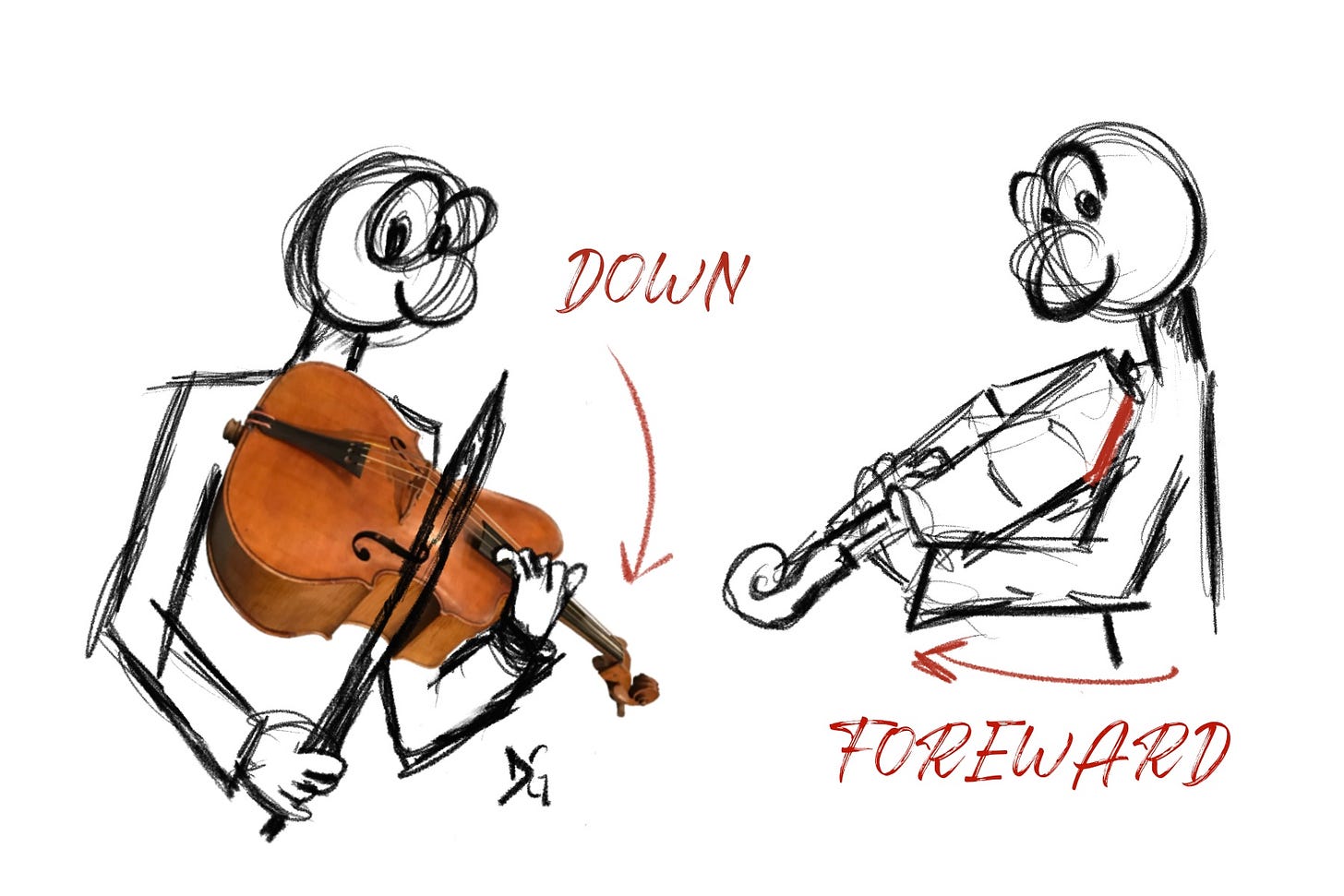

For the posture, the canting back is more intriguing. Because it is canting off toward the end button, at the opposite side of double basses and gambas, it is clear that it was meant as da spalla. Plus, the bottom pin seems to have a groove for the strap. I'm afraid I have to disagree with the museum's label, mentioning that this bent back was designed to place it under the chin. It looks very uncomfortable that way. Instead, it seems perfect for the position in which we play the Spalla, which requires the left hand and arm to be down and pushed a bit forward so that you can play with your bow up to the very tip, and when at the frog, you don’t risk your eye…

It looks like this instrument is suggesting to us the correct position to play da Spalla.

There still are many open questions about it. Being Italian, its provenience from Florence makes me curious. I cannot avoid linking it to the seven instruments catalogued as controviolino by Zorzi, Florence, beginning of 20th century, listed in the museums of Milan and Florence. Someone could say that instruments out of the standards in museums are instruments not played. Yet, why should one make seven of them with no demand at all?

Comments, news, hypothesis, ideas, thoughts are all very welcome in the comment section below.

Updates from our workshop

We are enjoying a warm summer, never too hot, thanks to a storm every evening. We live in the mountains in South Tyrol, so despite being in Italy, we now have no more than 23* C inside (without air-conditioned) and exceptionally high humidity of little less than 60%! It’s the perfect weather to glue joints, so we are preparing our woods for the winter!

Featured video of the week

Enjoy this Adagio and Allegro op. 2 n. 3 by Jean-Pierre Guignon, by Yun Kim and Francois Fernandez!