Leopold Mozart’s Violinschule is undoubtedly a milestone in violin literature, and this is because it is not the generic tutorial on music written by a theorist or addressed to amateur musicians, as were the treatises we examined before. This is a violin method written by a professional violinist expert teacher and addressed to colleague teachers. With his book, he wishes to indicate the proper way to teach in order to have violinists with good taste and not limited by their technical skills.

In the preface, he laments that adults are so often spoilt because of bad habits than even showing them the good way they can’t do anything about it, and forgetting those bad habits will require hours and hours of hard work with no guaranteed results.

So he recommends never to get to the following lesson if the current one is not more than perfect. Never move to the next step if the student is not ready. Editha Knocker, translator of the English 1937/1948 Oxford Press edition and great pedagogue (former student of Joachim, then assistant of Leopold Auer before opening her own school in London), comments that she feels this is a major difference between his way of teaching and the one used at her times. And this made me smile, as I think the same of how I was taught in the 1980s and how they do it today!

Leopold Mozart, born in Augsburg and the first son of an artist-bookbinder, was expected to bring on the father’s enterprise and maybe to escape this fate, he asked (and obtained) to receive a church education instead, at first in the monastery of his home town and then at the university in Salzburg. However, while there, he deserted theological studies and devoted himself to those of Logic and Law. On top of his education, he travelled a lot (with his family to raise young Wolfgang's career), increasing his critical sense.

For the biggest part of his life, he was vice-kapellmeister for the prince-archbishop in Augsburg, working as composer of church and chamber music and violin teacher of the choir boys. The image we have is that of a pedantic man. He was also controversial and ironic. His high self-esteem and his devotion to his son’s career were probably two obstacles in his career.

This introduction aims to warn the reader against the impulse of diminishing the description of the middle-range instruments as just cloudy. On the contrary, it certainly is to be taken as very precise, and not only because he is a violinist and Wolfgang’s father.

What strikes me most in Leopold Mozart’s description of middle-range instruments is the number of sizes unknown to me, especially if I consider my Conservatory education. But hey, is this not a reliable description of all those things we see in museums, and they don’t know how to catalogue them? It’s curious how there is no simply alto and tenor viola (the two that would be most familiar to me). Instead, there is viola, bassoon-viola, and hand-bass viola (Handbassel). I’m already not sure of what a bassoon-viola is. Still, the hand-bass viola, suitable to play the bass line on (when there are only treble instruments in the ensemble), seems to me the perfect fit for those small ensembles so typical of Saxony in Bach’s time. Church ensemble that could also play in the streets for a procession or also, why not, for village dances. Small ensembles with two treble instruments and a bass, a small bass easy to carry on a church balconade and comfortable to play in that tiny space, as we often see in iconography.

I suspect the word Handbassel had been overlooked until now, as this treatise is one of the most studied. I can’t avoid thinking of all those tiny basses in museums, like the Wagner in Lübeck or the Goldberg and the Hammig in Markneukirchen, and so many others, which were made right in the middle of 18th century, so perfectly contemporary of Mr. Mozart’s book. They don’t particularly fit in any of the labels we would give today, but I think they would perfectly fit the label Handbassel, as that’s what they are: tiny hand basses. The ending “-el” in old German stands for small, tiny.

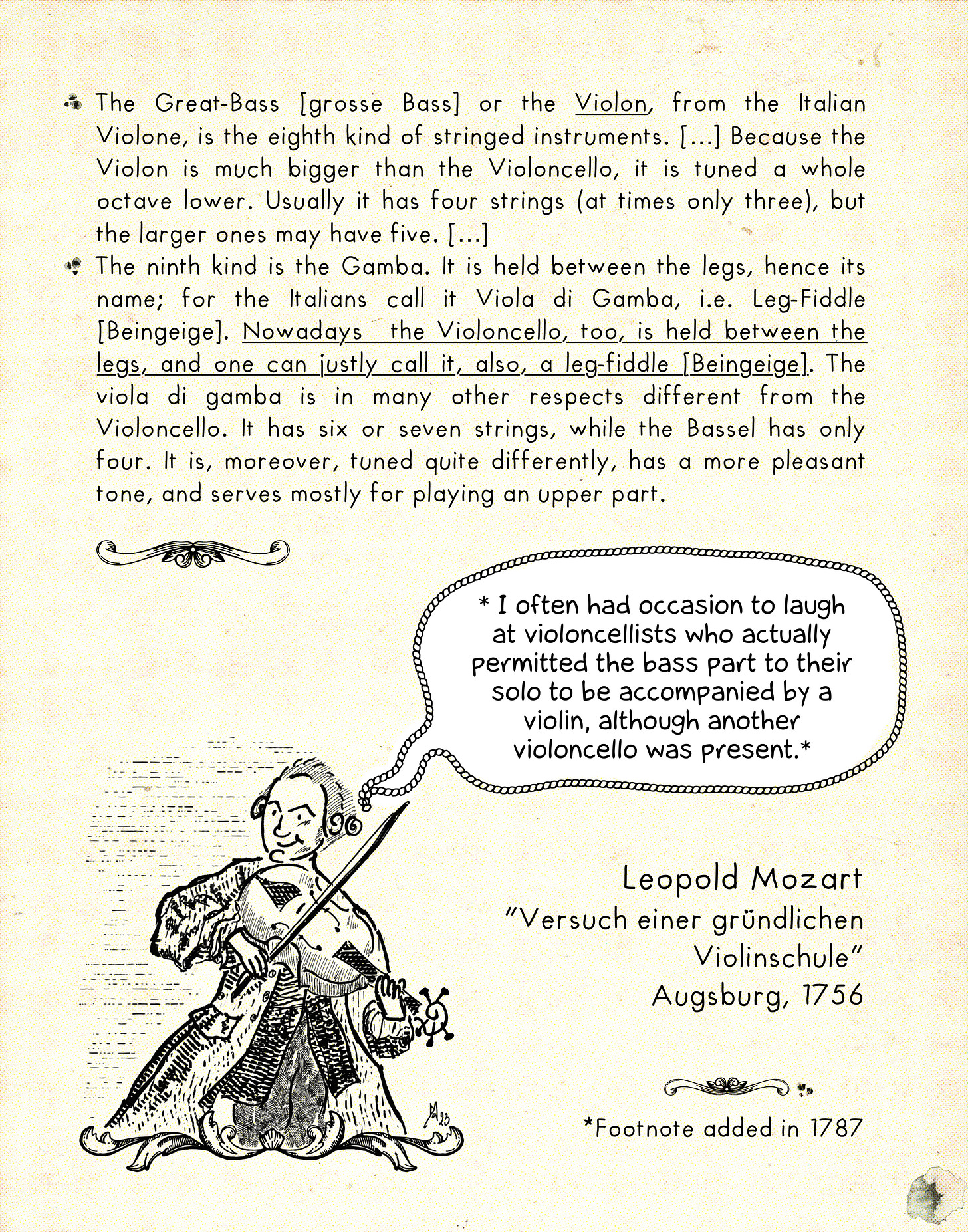

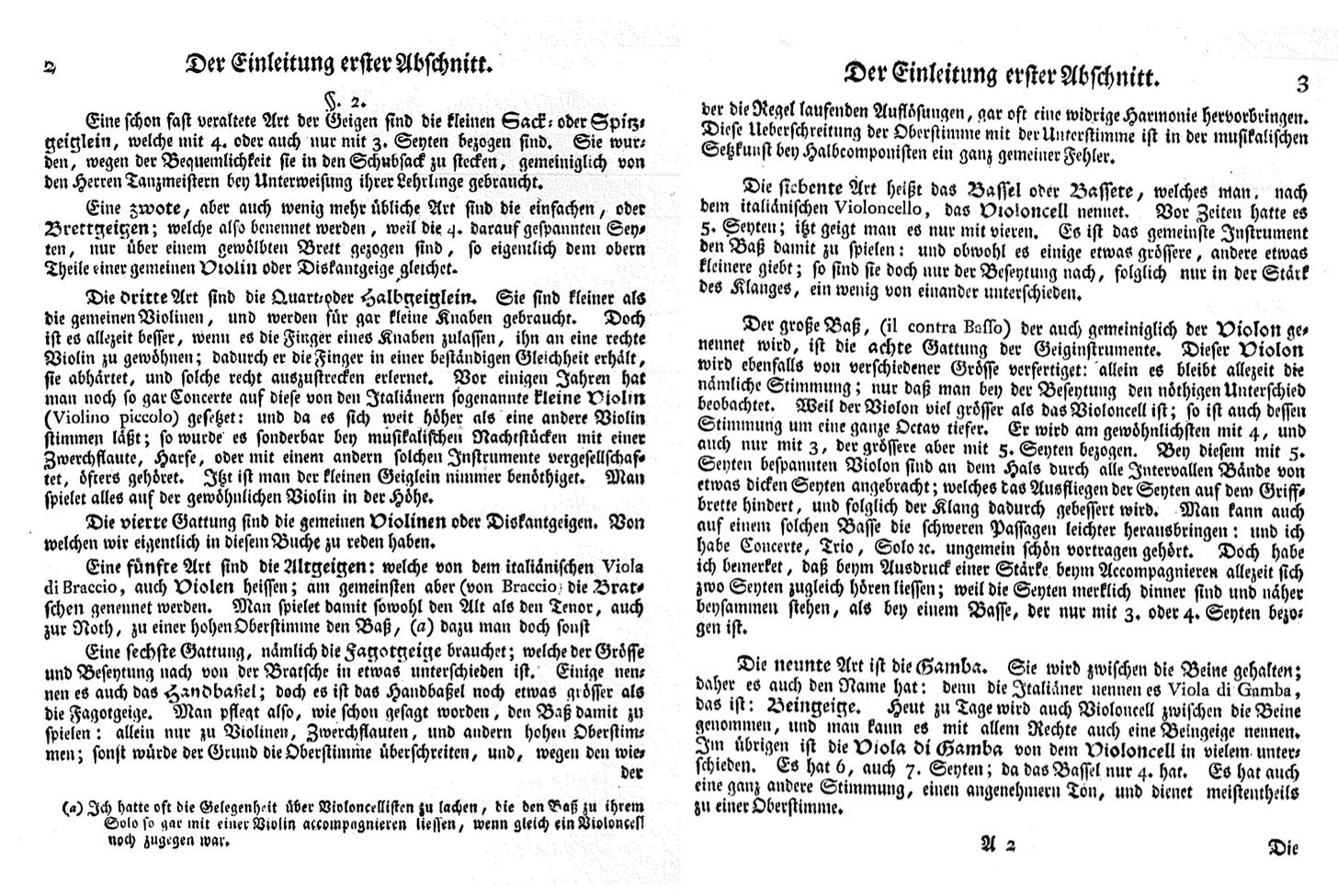

In the Gamba passage, there is the now famous quote: “Nowadays the violoncello, too, is held between legs, and one could justly call it Beingeige”. Does it mean that yesterday the violoncello was not played between legs? Or that today we also have this novelty, the violoncello, played between legs like gambas? We can’t be sure, as in the original German text, no commas are coming in our help. The first idea seems the most probable because, in the cello paragraph, he doesn’t introduce it as a novelty, he simply attests the Italian name for it.

On a curious note, the phrase I put in the speech balloon is a footnote that Herr Mozart added to his 1787 edition, the third one. He wrote to the editor that he only corrected mistakes from the previous editions. But, somehow, he felt compelled to add this phrase, to stress more something he had already stated in the text. It should have been such an annoying thing for him, this use of virtuoso cellists playing solo with treble instruments accompanying them! To us, this is strong evidence of how cello was used at the time.

Updates from our workshop

Daniela is recovering smoothly from her week at the hospital, while Alessandro finished the scroll of his cello.

Want to know more about our instruments?

Further readings:

Featured videos of the week

It's hard to say this video is already outdated! We need to make a new one in our new workshop! But as it will not happen that soon, here is it, once again, just because we still love this music!

And if you want something new, be inspired by this video in which the cellist Umberto Clerici is speaking words with the same clarity of a singer, in this beautiful transcription for guitar and cello of Arianna’s lament, originally for lute and soprano.