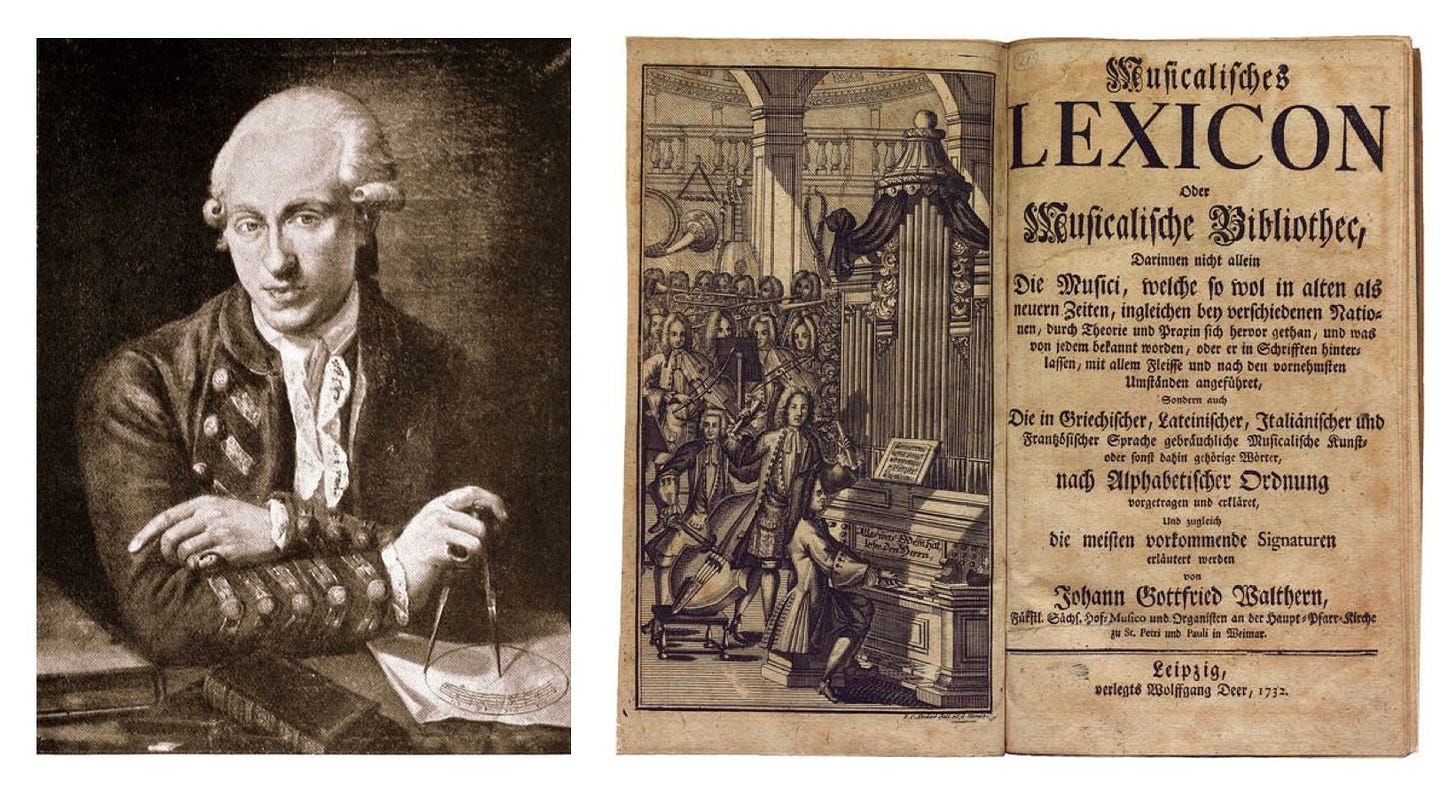

Johann Gottfried Walther, (born September 18, 1684, Erfurt, Mainz, —died March 23, 1748, Weimar), German organist and composer who was one of the first musical lexicographers.

From britannica.com

Walther grew up in Erfurt, where as a child he studied the organ and took singing lessons. In 1702 he became an organist at Erfurt’s Thomaskirche. After studying briefly at the local university, Walther decided to devote himself to music, especially music theory. In 1703 he began a period of travel, touring Germany and meeting such influential musicians as Andreas Werckmeister, a fellow theorist who took Walther under his wing. In 1707 Walther became organist at the Weimar Stadtkirche, and he retained that post until his death. In Weimar he also served as music teacher to Prince Johann Ernst, nephew of the reigning duke. Between 1708 and 1714 Walther formed a friendship with Johann Sebastian Bach, of whom he was a second cousin. During this time he wrote his Praecepta der musicalischen Composition (dated 1708, published 1955), a treatise of musical theory that included information on such subjects as notation, musical terms, and the art of composing, probably written as an instruction manual for Johann Ernst. From 1721 Walther headed the ducal orchestra of Wilhelm Ernst.

Walther’s compositions, which were highly respected by his contemporaries, include chorale preludes and variations for the organ, and organ arrangements of concerti by Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni, Giuseppe Torelli, and other Italian composers. Walther’s Musicalisches Lexikon, completed in 1732 (reissued 2001, with notes), was the first major music dictionary published in German and the first music encyclopaedia in the world to include biography, bibliography, and musical terms. It remains an invaluable source in the study of Baroque music. A volume of Walther’s letters was published in 1987.

Walther’s quote above is controversial for that “treated like a violin”, followed by a detailed description of the playing position, horizontal playing position, and that upper octave thing (as we already saw in Bismantova).

Rule to play the Violoncello da Spalla

Bartolomeo Bismantova’s “Compendio Musicale” is a tutorial book dedicated to “Signori Musici miei giorni” to contemporary musicians. B. B. was a cornetto player in the Academia dello Spirito Santo di Ferrara, the hometown of the Este family. It contains music theory, technical rules (like fingerings, breathing rules, and bowing rules), as well as helpfu…

The quote comes from a vast work written during his friendship and correspondence with J. S. Bach, but remained manuscript.

In Agnes Kory’s work (page 47)

It is not clear how the playing mode compares to playing the violin. If the fingering follows Bismantova’s diatonic pattern with large stretches between the fingers, it would surely necessitate a smaller instrument than what we regard today as the violoncello. Walther’s viola tuning, presumably referring to one octave above the violoncello, is also problematic. One is left wondering whether Walther is describing a very large viola which is used for bass parts, or if he is actually referring to an instrument which in size is between the viola and the cello. It is notable that Walther wrote his thesis in the year (1708) when Bach composed his cantata BWV 71: the elaborate solo cello part (in the sixth movement) does not need a C string, but goes rather high on the ‘a’ string. It is therefore feasible that, for this cello part, Bach used a small instrument with G-d-a-e' tuning. Bearing this possibility in mind, the question arises whether in 1708 some stringed instruments – which have been referred to as violoncellos – were in reality between the viola and the cello (in tuning as well as in size).

In Walther’s published and most famous work, the Musikalisches Lexicon, we have this image side of the title page, showing two large violas, 5 strings, played horizontally. They seem fastened to the neck of the players by a scarf. As they are two, they are probably not playing the obbligato part. One is reading from the stand, the other is ahead of it, so could one be playing the continuo and the other an obbligato part? Even this is controversial, but anyway, it’s a fascinating source.

Updates from our workshop

Should you be interested in trying our instruments, get in touch! They’ll be ready soon!