How we lost the ancient quality of gut strings - part 1

How the history of a small Italian village influenced our taste for music

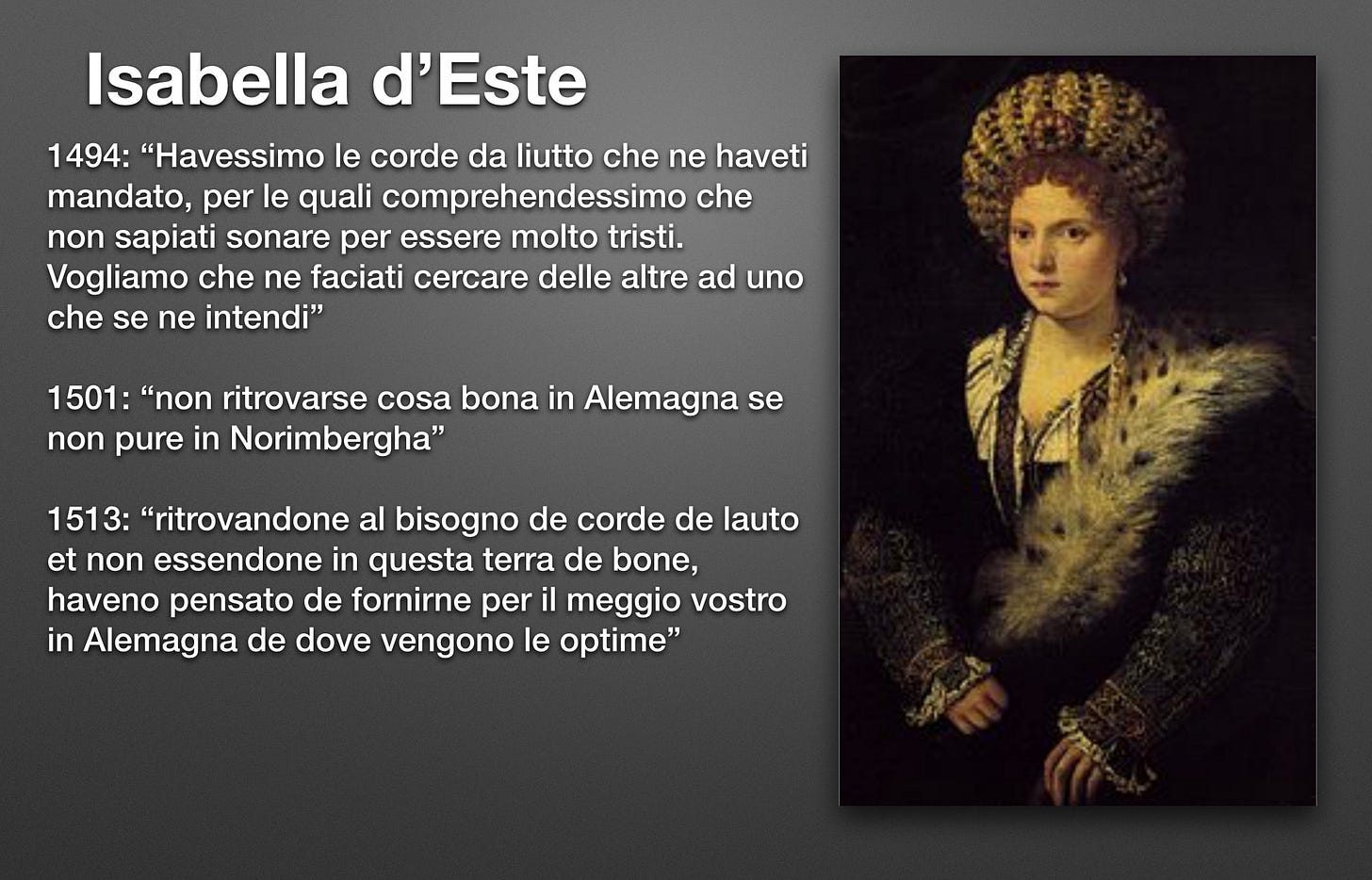

The Este ambassador in Venice, in 1494, received this sort of acid complaint from his noble lady Isabella: “We received the lute strings that you sent us, and we understood that you could not play as they were really sad (low quality). We want that you put in charge of finding our strings someone who can judge the quality.” However, and how frustrating was this for both Isabella and her ambassador we can only imagine, the best strings back then were coming from Germany through Venice, but even those were not good enough for her music practice!

In 1500 professional strings were made in Bavaria. As well as most high-quality instruments, as far as plucked instruments are concerned. Then, at the end of the century, from those regions, many artisans emigrated, establishing themselves in Venice, Bologna, Rome. Those towns were rich, animated by commerce, luxury, cultural movements and entertainments. During the periods that we call Renaissance and Baroque, music reached its highest peaks in Italy. (Will French readers excuse me here? Probably not, in fact, competition between France and Italy has been very high since then!) At least, money and acknowledgement were not unreachable goals for musicians!

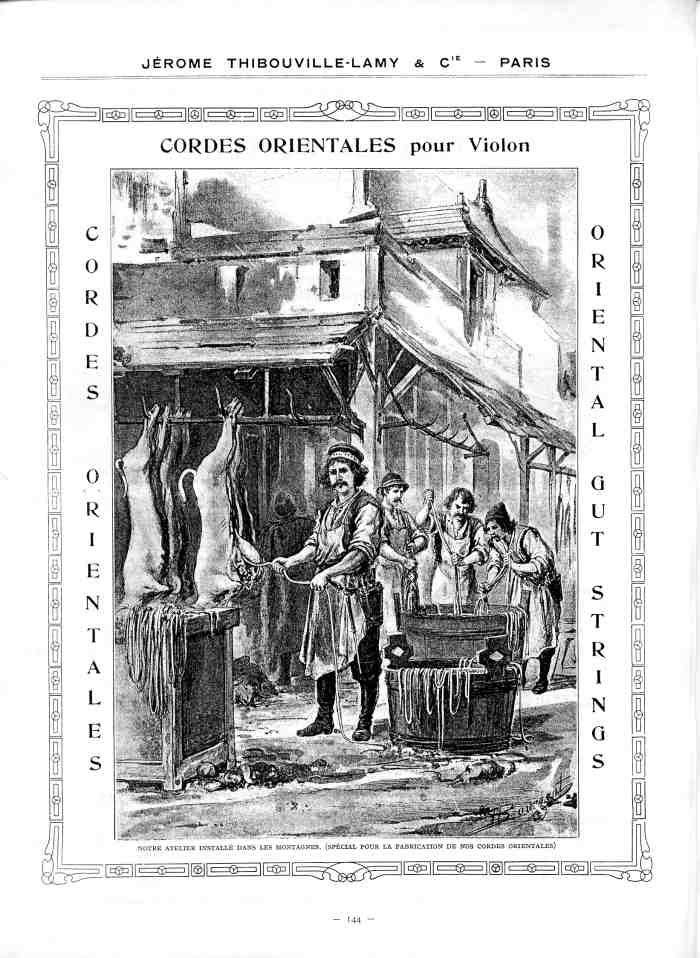

Gut strings makers are not always the best people in town. They deal with the business of slaughtering, they open sheep bellies while still warm, to pull out the guts from them. They are smelly. In a period in which violence was experienced daily and emphasised, gut strings makers were probably not among the sweetest people you could meet. I believe that one of them was emigrating from Bavaria with a certain urgency to hide and ended up searching refuge in the mountains between Ortona (the last port in Adriatic sea before sailing to the east, and an Augsburg domain) and Rome, in the region that today we call Abruzzo. I found no other explanation possible for the fact that, out of thin air, at the end of 1580 in the three small villages of Salle, Musellaro and Bolognano, flourished a production of high-quality gut strings.

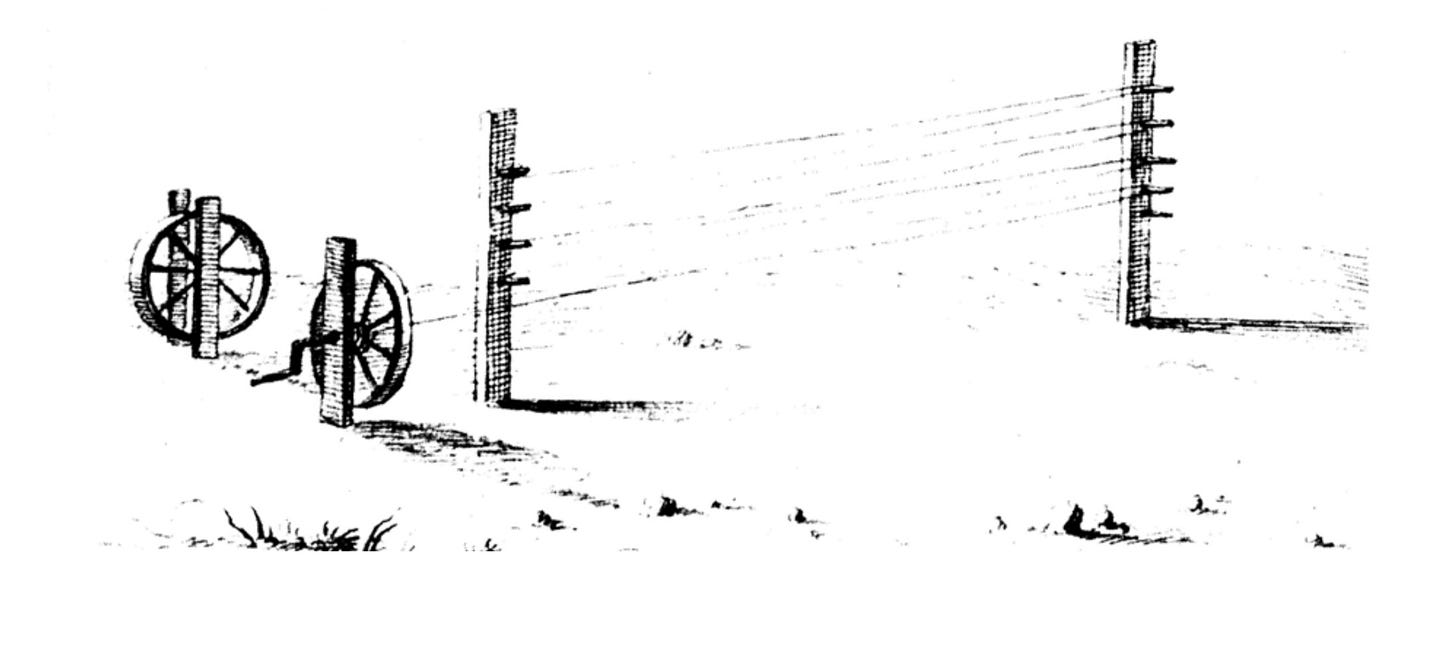

The industry soon got organised so well that the Italian gut string became the only high-quality gut string a professional (or a wealthy amateur) would use. String makers from those three villages moved to Rome and Naples during spring and summer, which was the season in which a great number of lambs were slaughtered (Abbacchio -suckling lamb- was the typical meal on and after Easter there) because lamb gut is very delicate and couldn’t be shipped on the mountains.

Being organised in corporations had huge advantages: dealing with suppliers of raw material and with customers was easier: during the XVII century, the String makers corporation in Rome was able to deliver single orders of 400.000 strings for the court of Spain. Each workshop, or factory in town, could employ hundreds of workers. We often tend to consider the baroque gut string as a product of a family-run small workshop, instead, it was a highly standardised product coming from a factory organised craftsmanship.

So, what happened that caused the Italian string makers to lose their hegemony in the European market around the second half of the 19th century?

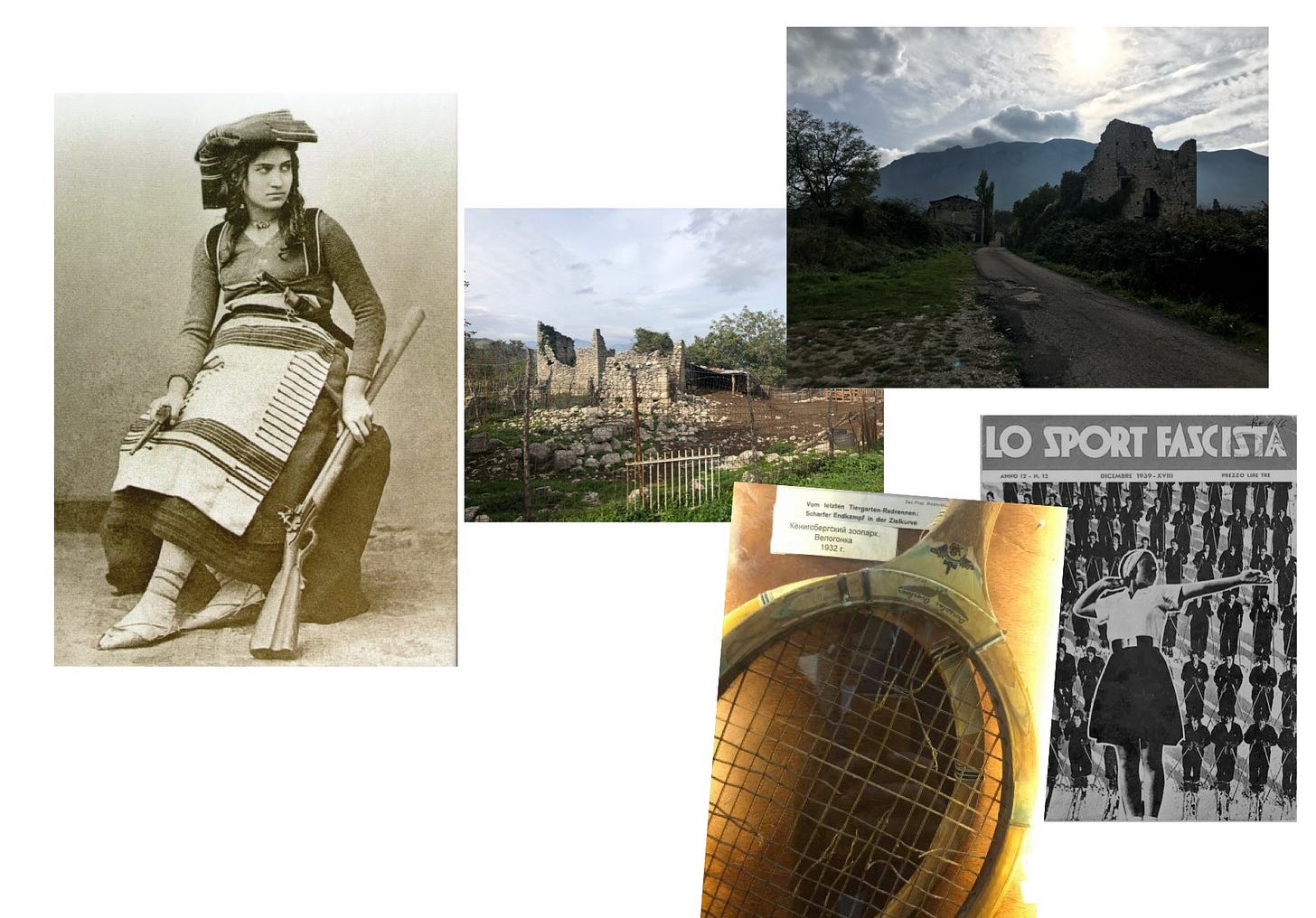

The wars for Italian unity were indeed civil wars in those regions, with the peasants (and in our case, string makers too) becoming brigands. They couldn’t understand why they should accept a new state, new laws, new taxes, new people, and they suffered hunger, the dismissal of old corporations and their traditional work organisation, their working contacts. One of the trophy brigands used to carry to the village when they managed to kill state soldiers was waving the victim’s intestines while entering the town on their horses.

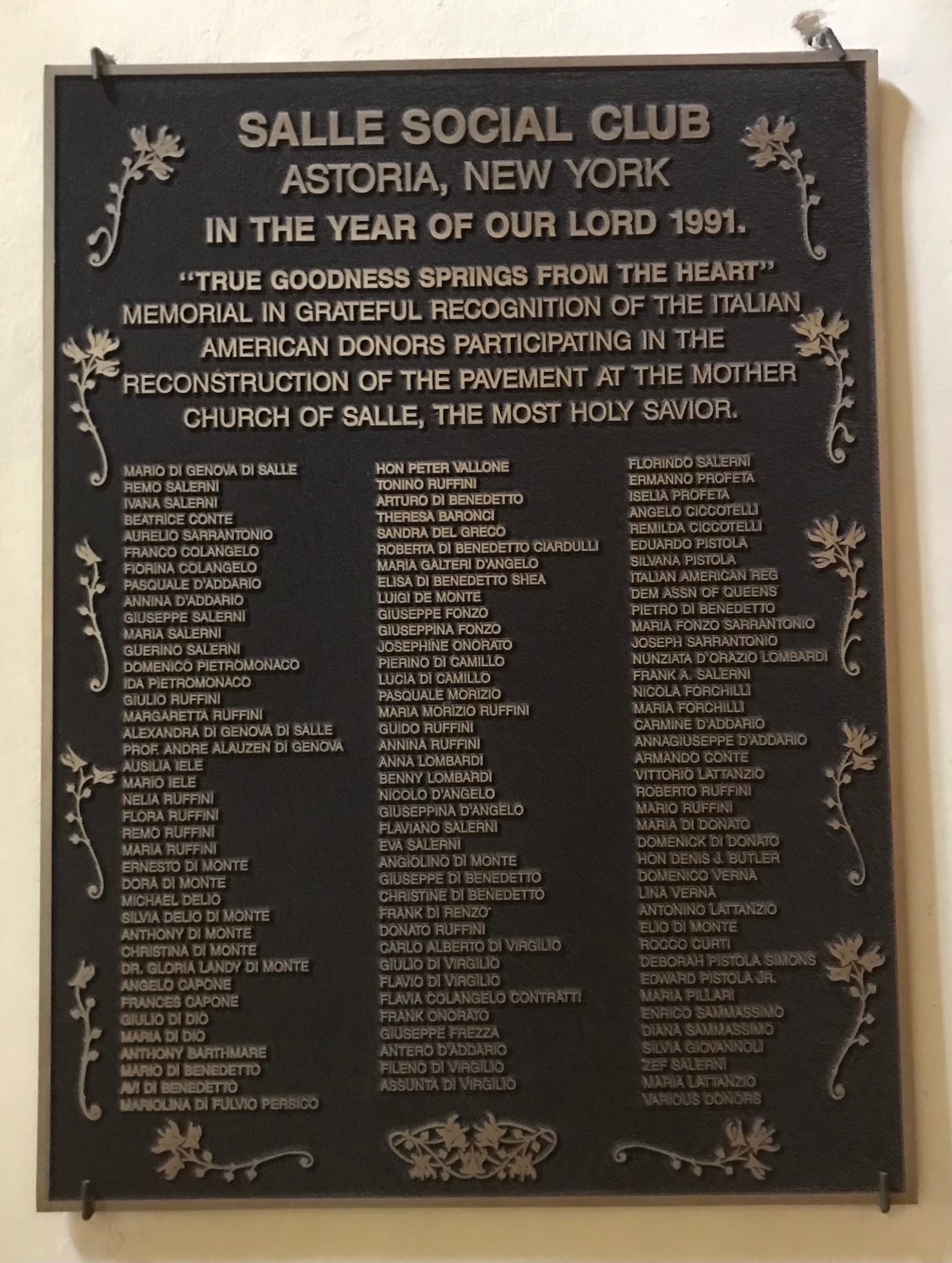

Earthquakes: catastrophic earthquakes destroyed the villages between 1905 and 1932, forcing many families to emigrate to America.

First World War: on top of the losses and damages of war, here comes the great demand for surgery thread, which has a different technology, being longer, stiffer, less twisted, perfectly polished, not vibratile as a musical string.

Fascism: music was often censored, dancing in public was forbidden, and sports were, on the contrary, supported. A sportsman does for a better soldier than a musician or a dancer. So no support for harmonic strings factories, but a broader and easier market (less demanding in terms of quality and variety of products) was opening: that of tennis strings. By the way, tennis and surgery require very similar technical characteristics.

War, Catastrophes, Politics. These three things changed in a few decades the standard quality of a gut strings, affecting the sound taste and the musical instruments set up. (Tennis racket pic courtesy of Dmitry Ponomareff)

I have put together a short video, less than one minute, for my talk last week at the Women in Lutherie First International Conference. It shows the difference between a well twisted and flexible string, meant for music, and a stiff, polished, varnished string, which could be used on a harp (modern harps developed at the beginning of the 20th century, so with this kind of gut - for them, too much sustain of sound is to be avoided, it’s a lot of hands work to stop it, so they need strings not too flexible), on a tennis racket, and even for surgery if we are speaking of maybe an elephant… They are actually two cello second strings.

The second string is a beautiful string as well, but it was meant for a modern cello, with high projection, modern neck, big body. A cello da Spalla is another instrument, it is extra-shortened, and because of this, it needs extra-flexible strings!

What has all this to do with Violoncello da Spalla?

…to be continued…