Four luthiers in a car (Germany upside down)

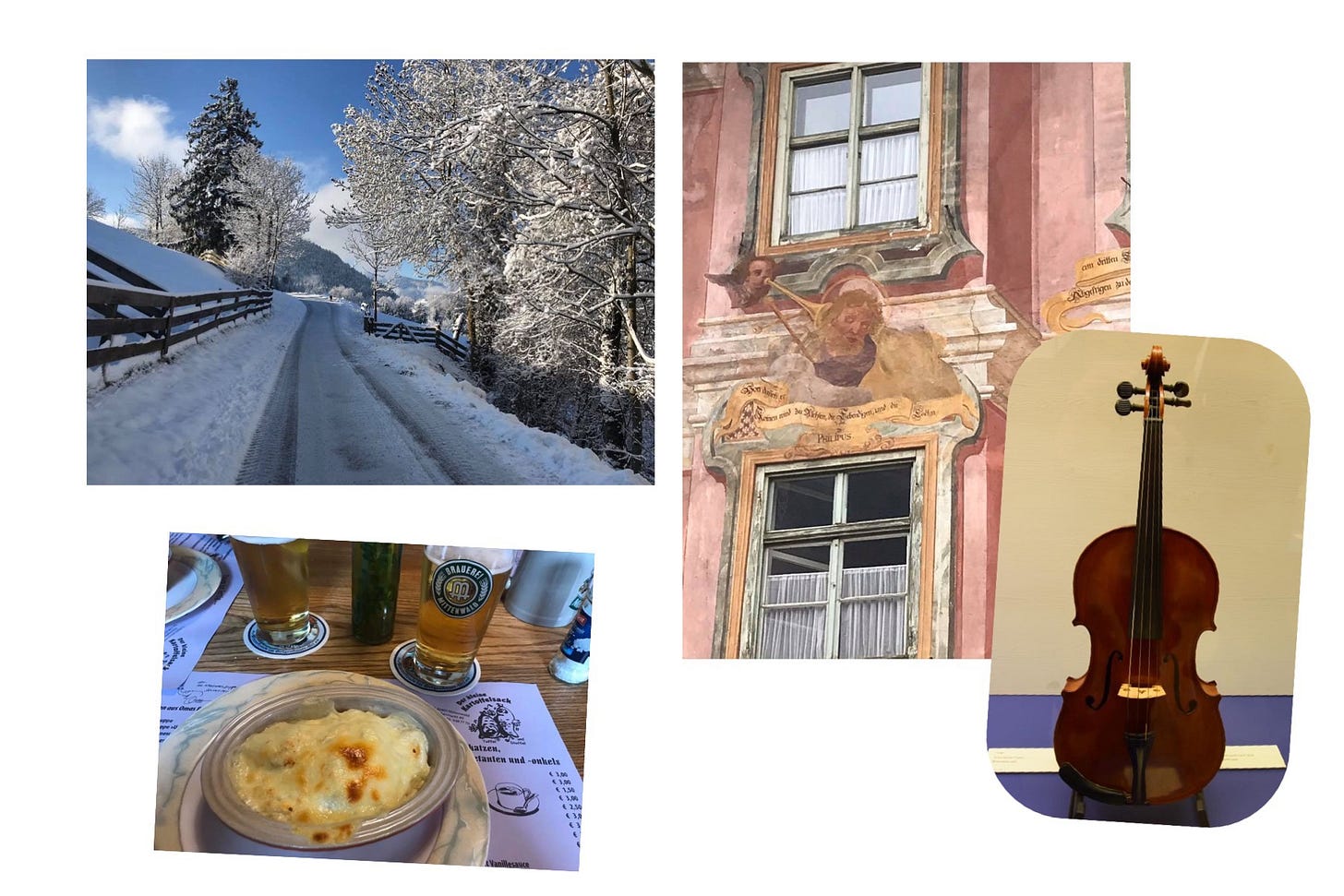

Precisely one year ago, we left home on one of those mornings in which you’d rather have some skiing than a whole day drive, but we had a research adventure waiting for us!

We didn’t plan it before, and it was just by chance that we stopped for lunch in Mittenwald. We had an appetiser of what was waiting for us: loads of German food and an oktave geige winking from a local museum entrance.

We had a brief stop in Nuremberg, where the Museum shows a notable collection of local makers instruments (between them, big cellos, small cellos, tenor violas...), and one of the best collection of German art.

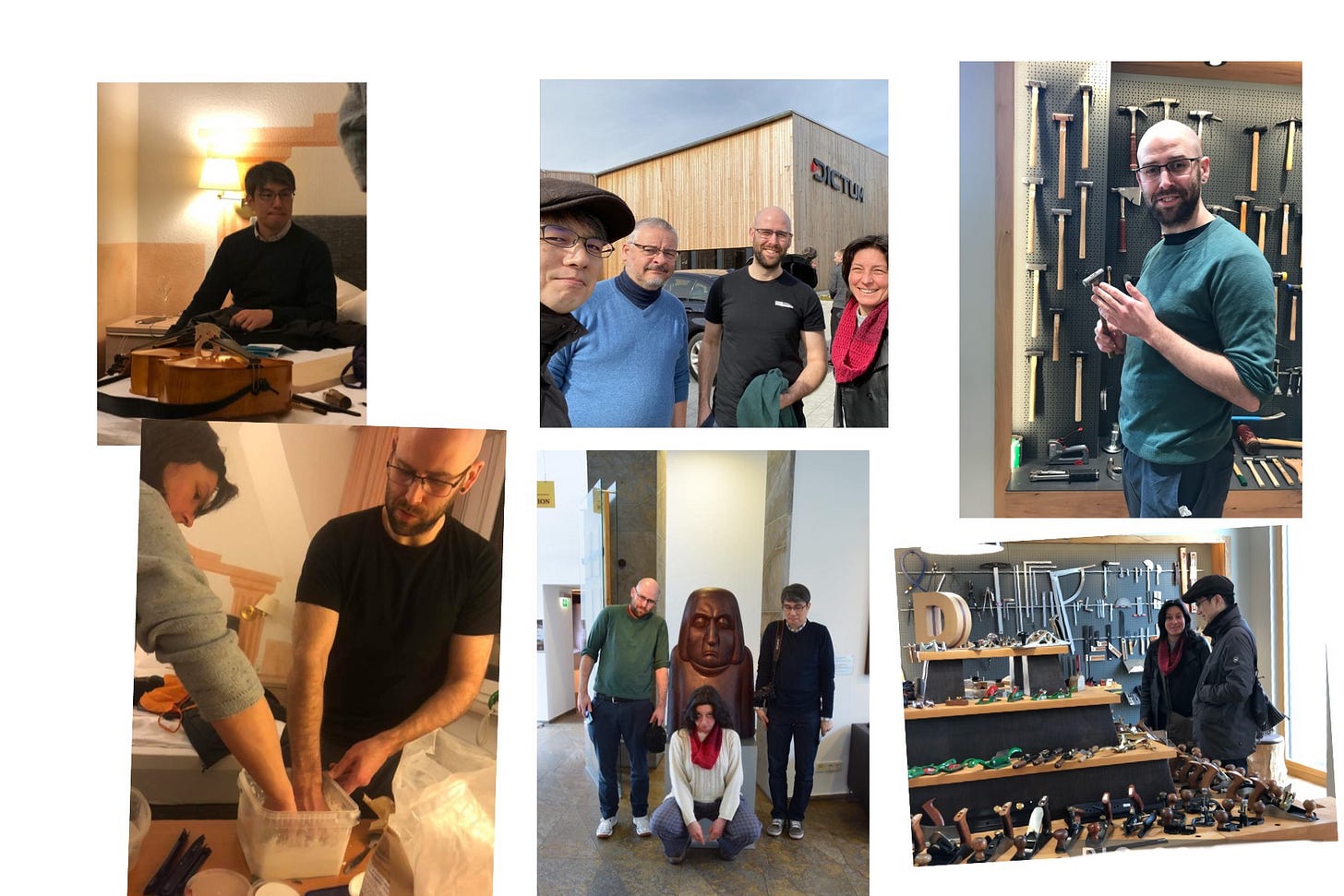

And we finally arrived in Hamburg, to pick up our friends: Takumi Takakura from Japan and Paul Shelley from England. We met in 2018 through a network of luthiers focused on da Spalla and hosted by Dmitry Badiarov. We nurtured a closer relationship later in my Gut Strings Guru membership, but this was our first time together. So exciting!

After a month of planning and anticipation, we were finally on the road together! Alessandro drove the whole way. I was planning, looking at maps, and reading documents (it was funny how being all in the same car, we started to find on the web documents we didn’t see before!), Paul was busy learning some new techy stuff, and Takumi was enthusiastically sharing fancy Japanese snacks with our South-Tyrol Schüttelbrot.

First stop, Lübeck, to study the Johann Wagner cello piccolo at the st. Anna Museum. This instrument is not regarded as something special despite its original neck (which made us so curious to plan the whole trip). It is not on show, and the curator Bettina Zöller-Stock was quite surprised by our interest. She gave us the warmest welcome (with some very special chocolate-marzipan, typical from Lübeck!) and left us with the Wagner for a whole day.

Knowing that it's neck is as short as a violin’s, we expected something Frankenstein-like. Instead, the eye is not offended at all because it's harmonical proportions are very carefully observed. It is not an instrument of high-level craftsmanship, and it has some features typical of popular making, but it was made from a skilled and long-time luthier because, on the other hand, it is very precise, not at all the work of an amateur. It makes me think that in the mid of the 18yh century, there was a demand for these instruments; it was not just a “curiosity” attempted by Bach and his friend, but a standard component in ensembles of travelling musicians or open-air entertainers.

Then we headed to Leipzig, where we had an enthusiastic welcome from Veit Heller, and we enjoyed a long talk with him. We had many questions, like: are the Hoffmanns original? Why do they look so different one-another? How and when were they modified? He had not only answers but many pieces of information and passionate stories to tell us! (there’s more I this in my last article, here).

It was exciting for us to compare, side by side, our Badiarov model with the original Hoffmann, and we all noticed how similar they are, despite being the Badiarov model more elegant.

Leipzig Museum has on show several “non-conventional” instruments from the 16th to 19th century. They have a “Violoncello da Spalla”, by L. Arcangioli, Florence 1825, which seems dropped out from a Dalì painting. A violoncello piccolo, five strings, by C. G. Klienger 1775, and a tenor violin, six strings (!), by G. Picinetti, Florence, 1682. It’s one of those museums in which one week would still not be enough...

We already had different plans, which, actually, were not so productive as these two days. Partly we were already tired and loaded of information to digest, and partly because the covid alert was spreading.

We went to Eisenach, to the Bach Museum, which has on show some instruments from “the period” of bach. It’s more a curiosity museum, with some good pieces but not really researchers friendly. Unfortunately, the man in charge of the collection was away the whole week, but we were told we could see the instrument anyway, from the windows. What we were not told was that the room with the collection is open only for half an hour a day, during the demonstrative concerts. Just by chance we were there on time, we did our best not to disturb the concert with our cameras' clicks, but it was not a comfortable visit.

We then went to Nuremberg, but the covid restrictions imposed the cancellation of our meeting. We could only visit the collection, ask questions on the telephone with the curator, buy some technical plans. We wandered around for a couple of days looking for woods and tools, but with no success. We went as far as the border with the Czech Republic on the south, and we then left our friends in Munich, heading home with the menace of the most severe covid controls. However, there was none on the way. And, fortunately, we were all safe and healthy even after the trip!

What were our major takeaways from this trip?

- being exposed to this wide variety of instruments, all going under the name of violoncello, was a good refresh and a memento to look always with an open mind and a child’s curiosity. It’s too easy to discharge something with the label of extravagant, or folk, or forgery.

- if we were asked to make a good violoncello da Spalla after the originals in museums, something the most similar to what Bach had at home... we would end up with a Badiarov model. Watching the originals, we could appreciate so many common features, and most of all, respectful solutions for those details that need a different solution, all crafted with ancient design knowledge and dressed with elegance. If we started our trip with the idea of searching for something different, more “historical”, we returned home totally convinced of the Badiarov model's value as the respectful and historically informed realisation of this instrument.

- the value of the group: we are so grateful that we could make this trip together. We shared ideas, learnings, documents, laughter, meals and also weariness (well, actually, Paul never seemed to be tired, he could go on making casting during the night in his hotel room, even after a whole day around, a dinner and few beers!). We arrived home with a greater value than expected.

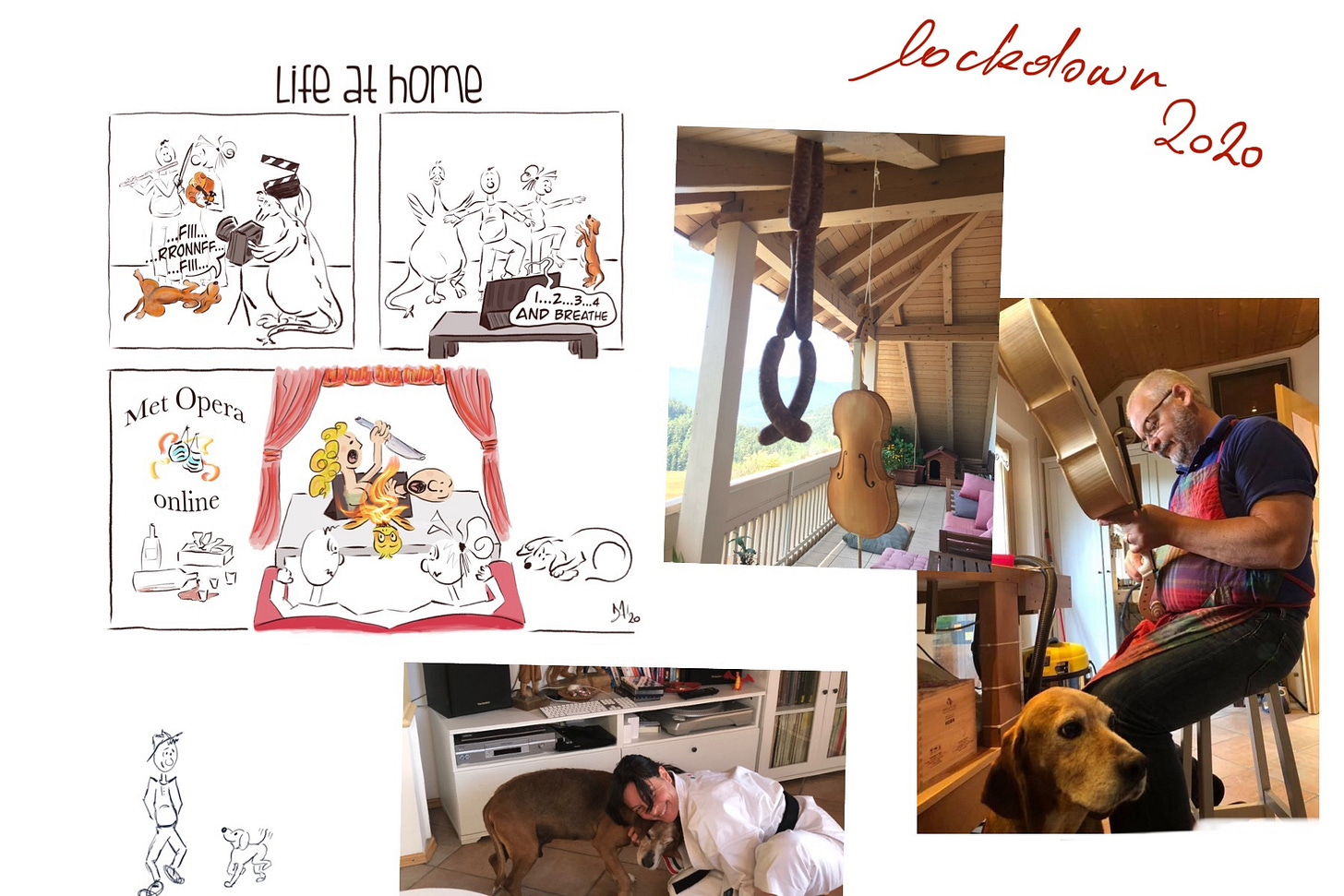

We were indeed fortunate to have such a recharging experience before the year of lockdown.

Thank you friends, we are very grateful!

Ps: did I mention ancient design knowledge?

This issue is already quite long, so I won’t take the space here to explain in details what it is, but in a few words: have you ever been into one of those ancient theatres, open-air, like Greek or Romans? There is a perfect acoustic there. If someone is whispering on then stage, you here with clarity from the top of the steps on the opposite side. If you play there, you don’t need to force at all despite being open-air, and you can hear everything around you. How did they do that? Using harmonical proportions, that is musical intervals measured on a monochord, to set the building proportions. And what has this to do with violins? Violins were designed in the same way before Stradivarius. Nobody knows why, this knowledge got lost, and copies were more on fashion than originals. This is a story that goes from 17th-century treatises and Palladian era back to Vitruvius and even more to the ancient Greeks...

News from da Spalla world

Well, this seemed to be a quiet week, I have no breaking news to share this time. If you do, or you want to be featured here, get in touch!

Updates from our workshop

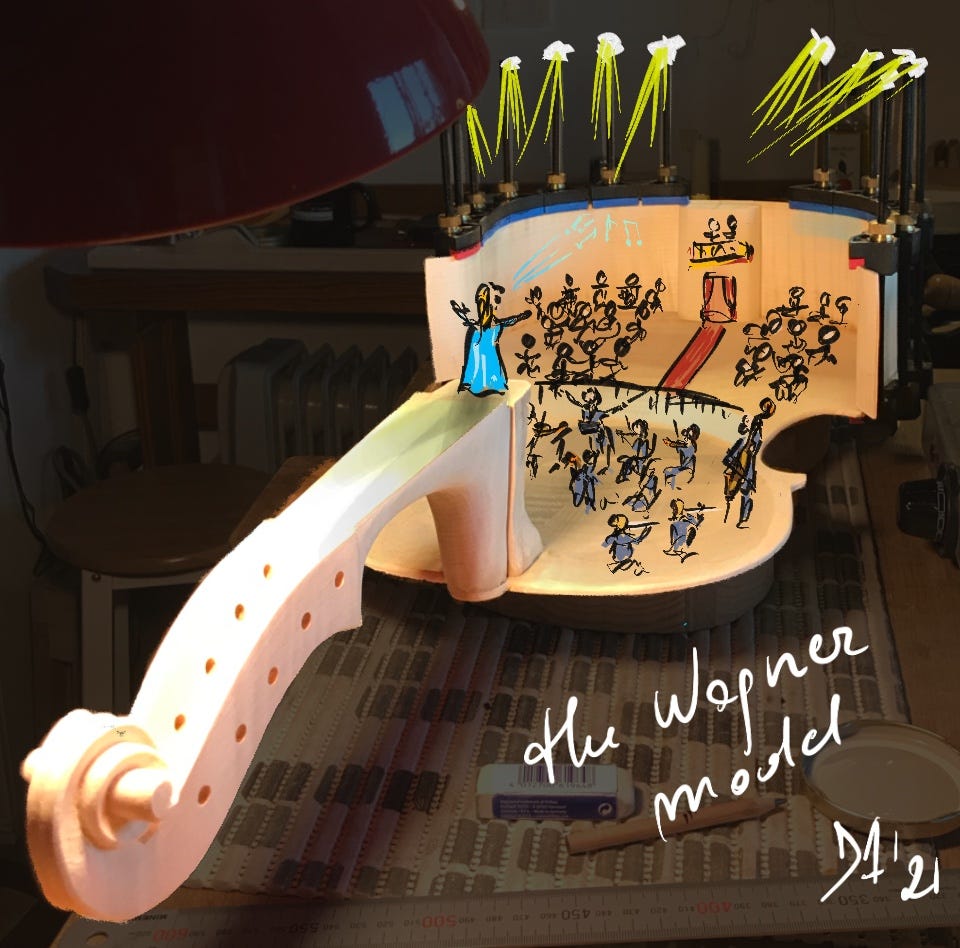

Alessandro injured his ankle this week, he will be fine very soon, but we spent time at the hospital instead of in the workshop. However, the Wagner is starting to get shape. It has floor and roof at least (and yes, no mould and no corner-blocks).

Featured video of the week

This, which I consider the most legendary video of all: Brandenburg third with three Spallas: Sigiswald Kuijken, Ryo Terakado, Dmitry Badiarov.