Did Violoncello da Spalla live an underground life up to the 20th century?

There are so many originals made in the 20th century in museums that it’s hard to ignore the question

This article is an article of questions more than answers, and I would appreciate getting answers (or more questions) in the comments!

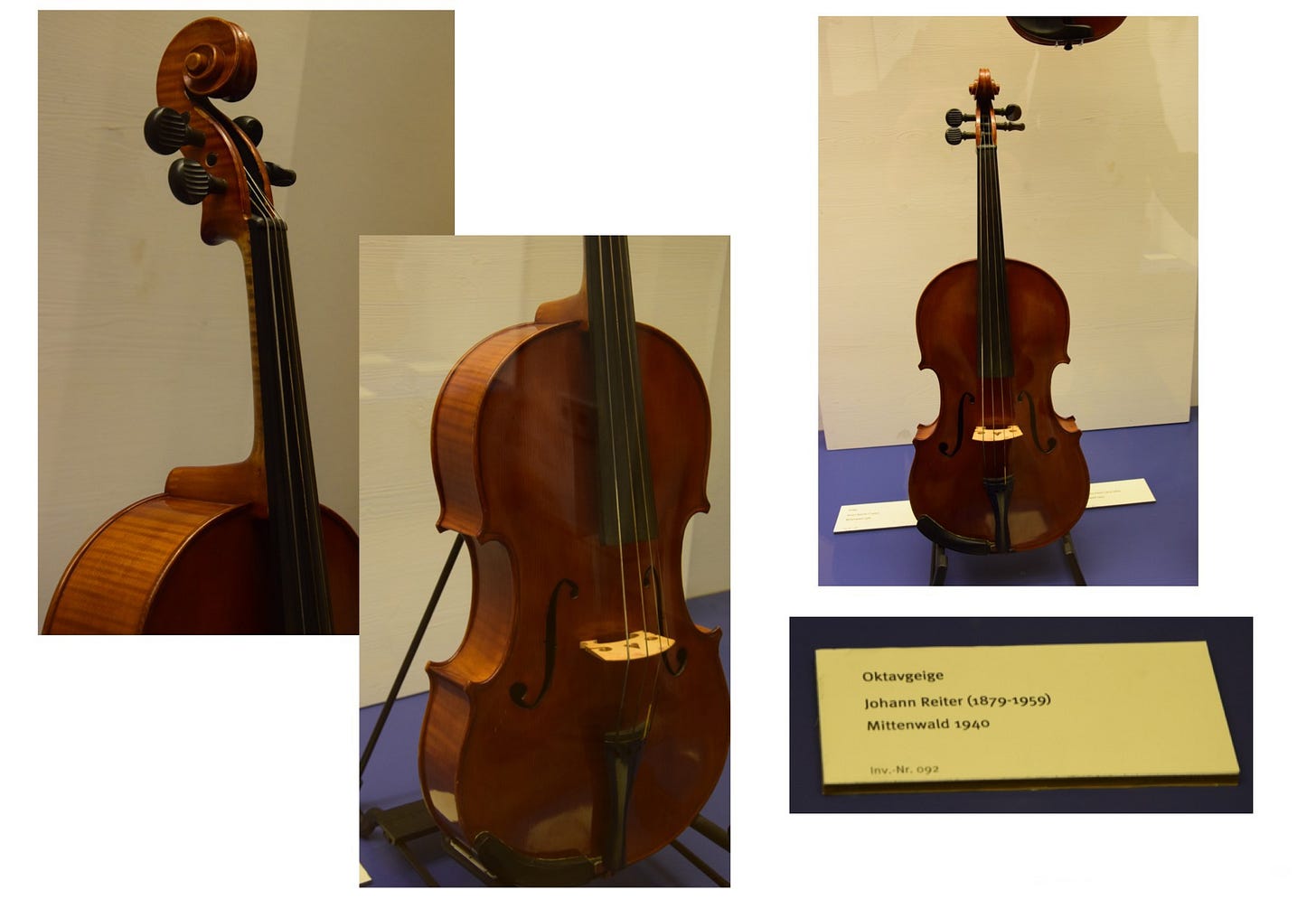

In March 2020, we went on a road trip to Germany, visiting several museums, and we stopped for lunch in Mittenwald. We visited the small museum there, and just at the entrance, behind the welcome desk, there's a showcase featuring a four-string small cello.

As small as ours, that is to say around 45 of body. We asked: “Oh, what’s that?” And the man at the entrance answered as it was the most common instrument in the world, “it’s an oktave geige!”. The instrument was made in 1940. Whom for? In which ensemble, on what occasions was it used?

In the many times cited article by Agnes Kory, she enumerates several instruments in museums built in the 20th century and not catalogued as children cello:

Seven instruments by Zorzi, Florence, made between 1900 and 1914, body length between 52.5 and 54.7 cm, are preserved in the Museums in Milan and Florence and catalogued as controviolino, tuned GDAE.

In the Paris museum, there’s a five strings cello from the 19th century made in Mirecourt, 58.5 cm body length, and another one made in Barcelona 1933 by Ramon Parramon, 53.5 cm body length, four strings. Both of them have ribs between 8 and 9 cm.

In Markneukirchen museum, they have five instruments made between the second half of the 19th century and 20th century: ribs are between 4 and 8, three of them more in the viola range, one on the cello piccolo range, and one right in between. Body lengths are between 45.4 and 47.5.

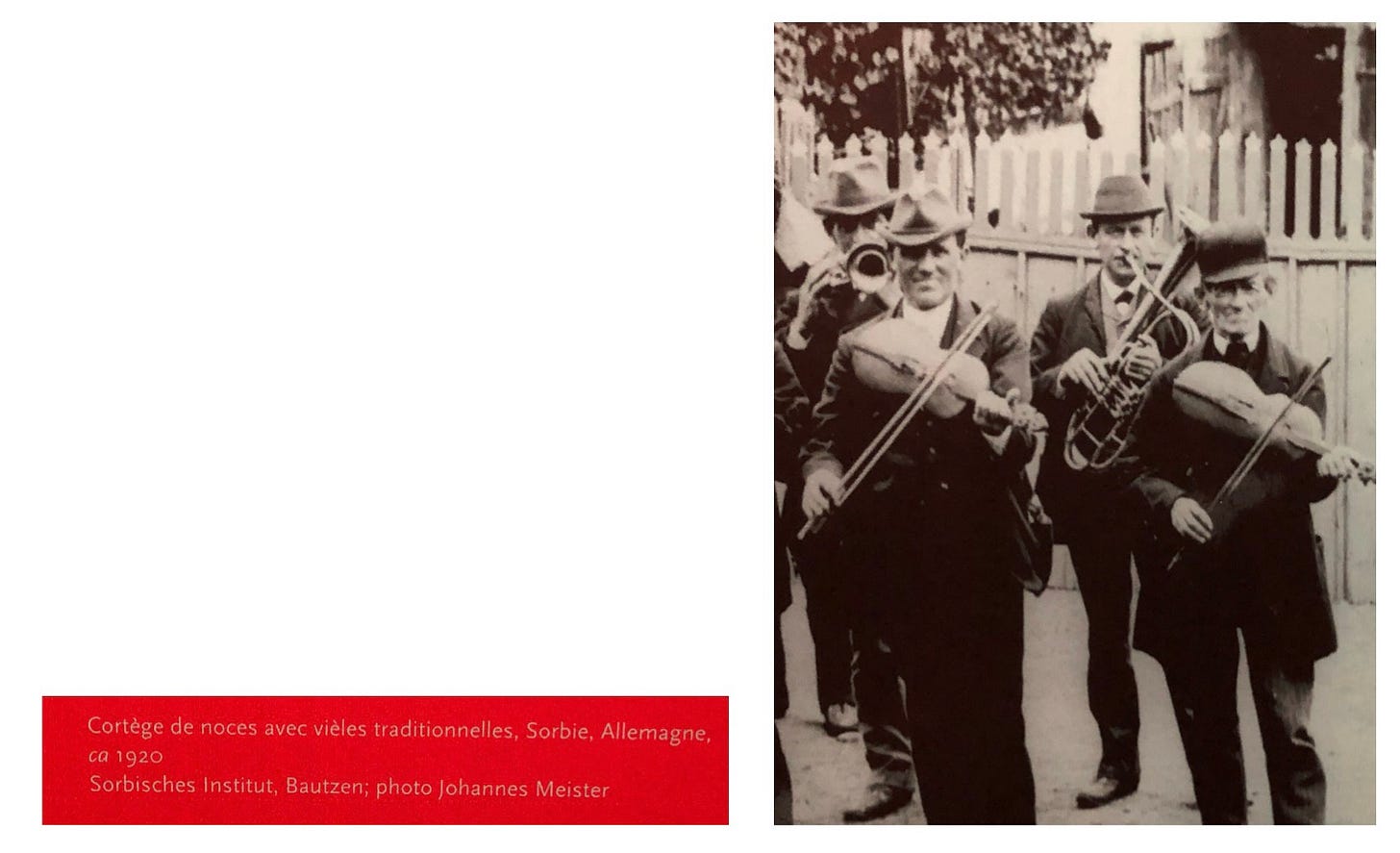

Those instruments do not match the standard measures of the classical quartet of the 20th century. They are just in between. We were raised in a conservatory, so we studied the official musical culture, and we never heard this middle size mentioned. Yet, we are speaking of recent instruments, something that easily our grandparents would have met. But on which occasion? We’re they used only in popular music? In Haus Musik? Clearly they had a market. Who would make a nonsense instrument just to get it into a museum?

Is it possible that we, raised in the short-sighted official classical tradition, lost a pretty big part of the story? Or that the small cello (or tenor cello), instead of disappearing under the pressure of the official classical music culture, simply made a step on a side?

Updates from our workshop

We have two cellos da spalla on the bench now. Each of us is working on his project. I started from the neck, while Alessandro decided to start from the ribs, so we don’t need to use the same vices all the time. Working in two on the same bench and with the same tools requires some coordination, but I guess that our life as orchestra players trained us for this. Don’t forget to follow our progress on Instagram!

A bit an off-topic news: Alessandro this week was busy as his orchestra is accompanying the final stages of the Busoni Competition, which is a important piano competition held here in Bolzano every other year. He is the piccolo and second flute player of the orchestra, for 43 years now.

If you like, you can follow the final round this evening at 20.15 CEST (GMT +2) at this link (he will play only in the Rachmaninov 3 concert, with the first candidate):

https://www.busoni-mahler.eu/competition/en/pagina-busoni-en/

Featured audio of the week

From a blog post by Maria Popova:

One midwinter day shortly before the pandemic paralyzed the world, Clemency Burton-Hill — an underground London garage DJ turned BBC host turned creative director of America’s oldest public radio station for classical music, and a lifelong lover of Bach — suffered a catastrophic hemorrhage in her left frontal lobe. She was thirty-nine, her children one and five. She survived, but was left unable to see, move, or speak. [...] Multiple surgeries and weeks of rehabilitation began restoring Clemency’s comprehension and sight, but the right side of her body remained paralyzed and her speech voided. Slowly, slowly, the words started forming again out of the primeval matter of the mind. [...] At first, with her life so brutally transformed, she found it difficult to even listen to his music, hearing in it the echoes of her former life and former self. But she eventually came to see Bach for what he always had been and always would be — the existential soundtrack to aliveness itself.

[…] With her hard-won words, she invites the voices of people from various walks of life, people who all play Bach daily to move through their own very different and differently challenging lives.

From Clemency herself: “It has been so difficult to even listen to my beloved Bach over the last 18 months but as I gradually, lovingly, find my way back to Bach it is so inspiring and comforting, even reassuring, to know that meanwhile, every minute of every day, someone is playing his music somewhere on this planet. Long may that continue”

As violist Robin Ireland says: “It’s an incredible piece of good fortune to be a musician in difficult times, because it is a source of continued connection with life and confort”

I feel deep gratitude to play and make an instrument so strictly connected to Bach

At this link below, available only for 19 more days, Clemency’s work: