Are the Hoffmanns fakes?

Fakes or 19th-century forgeries, let’s consider this idea from a closer point of view

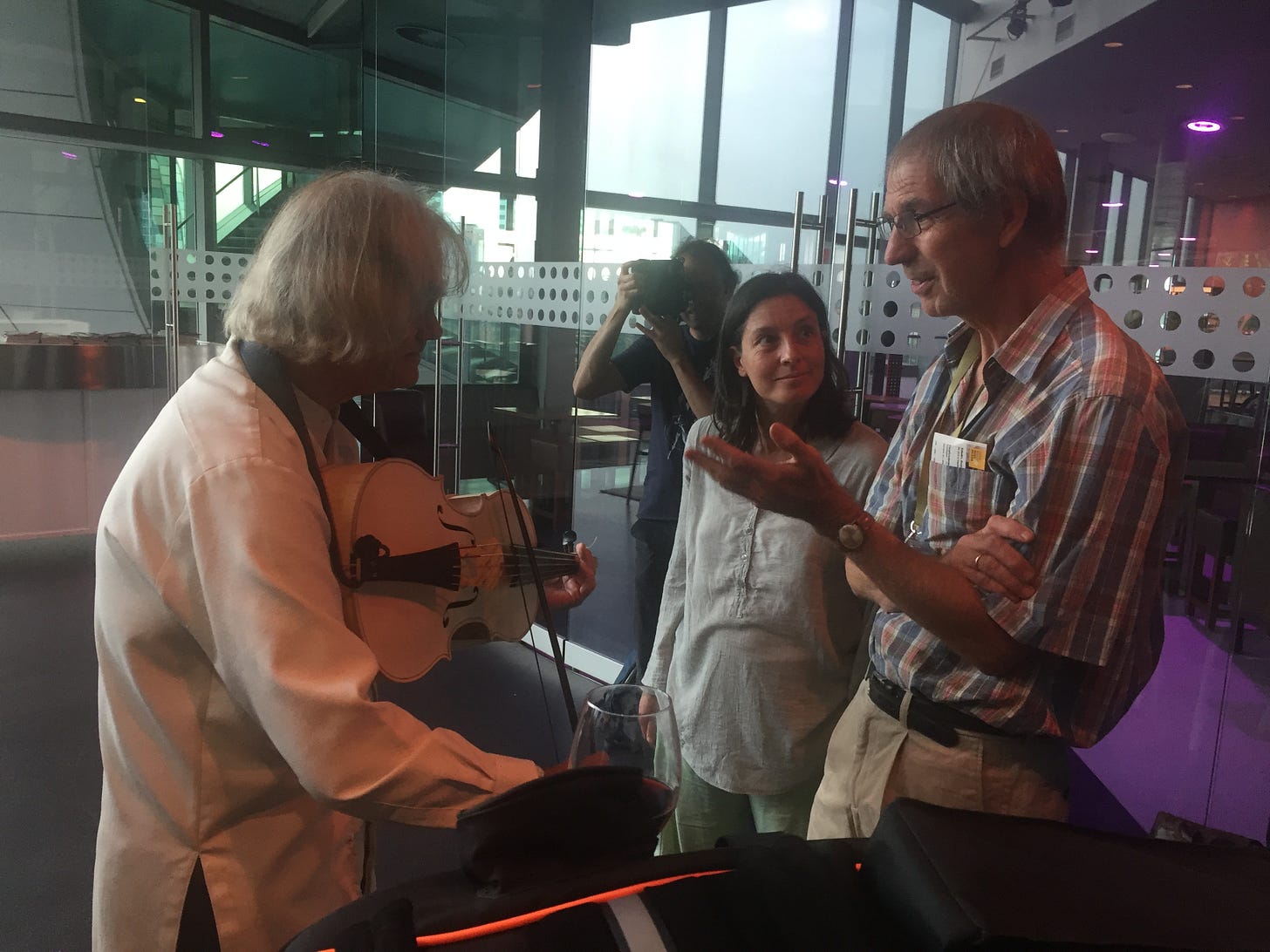

In the late summer of 2019, we completed our first Violoncello da Spalla, and we decided to go for a road trip to make up our mind about it. We went to Utrecht to a baroque violin symposium, so we could show it to as many people as possible and have feedbacks, and on our way back, we stopped to Brussels to see and measure an original.

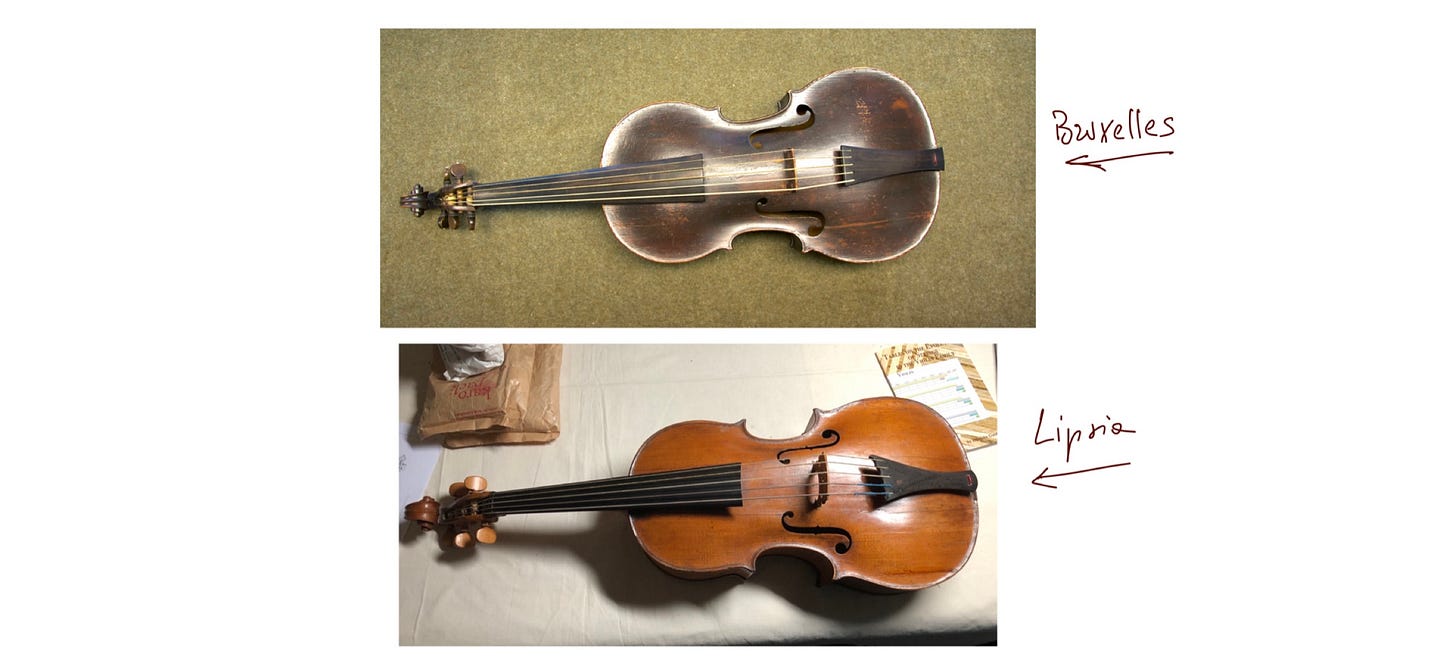

Brussels seemed the obvious point to start from, as it was there that also the revival of Sigiswald Kuijken and Dmitry Badiarov began. The Musical Instruments Museum preserve an original J. C. Hoffmann, that same Hoffmann who was a friend of Bach and was later mentioned with him as co-inventor of the “viola pomposa”. Well… I have to admit that at first sight, we were deluded. One cannot say it is a beautiful instrument. The varnish is dark and opaque, and the original neck, still there with its two nails, was modified into modern shape and angle. Clearly, whoever did the job was not paid enough to do it with love. The varnish on the neck is very poor, and the sides of the (modern) fingerboard are painted with what looks like a cheap black lacquer.

A few months later, we went to Leipzig Grassi Museum to see their Hoffmann, and to our surprise, this one was beautiful! Badly deformed, modern neck, but bright and translucent varnish.

At a first impression, someone with a not trained eye could be sure they have nothing in common. However, when you put them side by side, their close relationship is evident. We asked the opinion of Veit Heller, one of the authors of the book “Martin und Johann Christian Hoffmann”

and he was very straightforward in affirming they are both authentic.

He considered:

1. Measures

2. Varnish

3. Labels

4. Craftsmanship

1. We have measures of five 5 strings cellos piccolo/pomposas from Hoffmann (on the same book, page 213 - two of them are now lost), and their measures are so close to show with no doubt they were made using the same mould. They differ in millimetres, which is something that happens even working with a mould.

2. The varnish is coherent with that of other instruments of the same period in the workshop. The bright translucent varnish was at a certain point substituted by one dark and opaque, following the fashion of the bohemian instruments, which were diffused and appreciated in the market. Its opacity may have been exalted while ageing even by the oxidation occurred cooking the varnish in an iron pan (from Paul Shelley).

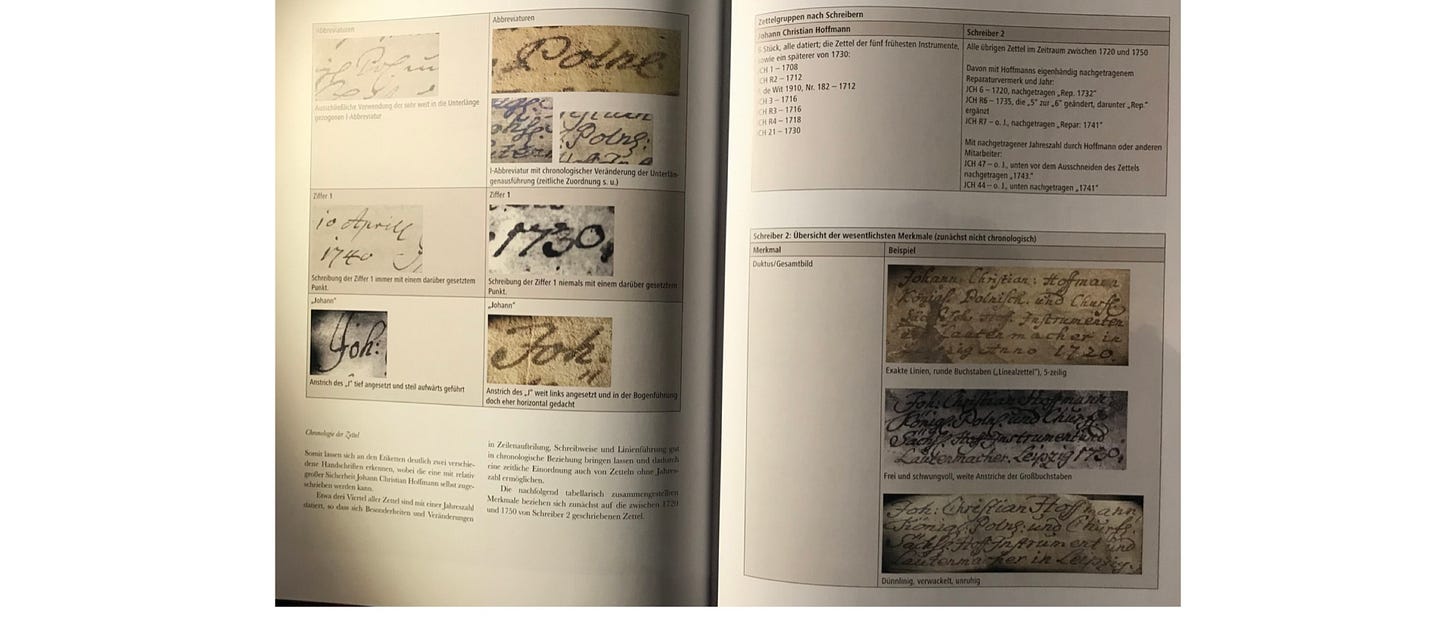

3. Labels: Veit Heller passed more than one year with all the labels printed and stuck to the wall in front of his desk… until he could put them in sequence and identify what was original and what was not. When Martin Hoffmann was alive, labels were written in the workshop. However, when the elder luthier died, Johann Christian commissioned more elegant labels from a calligrapher. It is possible to follow the evolution of labels even thanks to a technological upgrade in the nibs used: right in those years in Leipzig was introduced an innovative nib made in glass, which gave a more regular line, similar to that of a gel pen today. Details about this in the book mentioned above.

4. Craftsmanship: Johann Christian Hoffmann was the only authorised luthier in Leipzig. The municipality gave the license for this job to one man, and in his workshop, he hired other men to follow the needs of the whole town. In Hoffmann’s workshop regularly worked his brother and his son, together with other apprentices. So the fact that the Brussel pomposa seems to be done by a less skilled hand is not at all proof of a lack of authenticity. It is, in fact, a characteristic of the instruments coming from the Hoffmann workshop in those years.

Mark Vanscheeuwijck brings on the table two other factors to say that these instruments have no historical value.

1. The neck

2. They cannot play tuned at a cello octave without using double wound strings, which, according to him, were invented only after 1760.

1. It is indeed a pity that we don’t have a viola pomposa by Hoffmann with the neck in original condition. Still, unfortunately, this state is so common for 18th-century instruments that having the original neck in original shape is a rare exception. I don’t think this is a good reason to exclude the Hoffmanns from being taken into consideration as documents of how music was made in Bach’s time (and home).

2. With a high twisted and flexible core, they can play even with a single wound string. And with no significant effort, as I show in this video and I already discussed in a previous issue.

The Berkeley’s Hoffmann was once said to be the property of J. S. Bach, while one of the Leipzig lost ones was owned by a Thomaskantor from 1822 to 1892. These two assumptions do not prove anything, but the second is a fact and comes from long before the spreading fashion of the Violoncello da Spalla, so it’s not likely to be manipulated for any reason…

Next week I’ll show how, being the Hoffmanns fakes or not, history doesn’t change… stay tuned!

News from da Spalla world

These are just the first stages of a newborn character. Next spring I will release a book on Violoncello da Spalla and he will be the host, introducing the readers to the story of our fabulous instrument!

Updates from our workshop

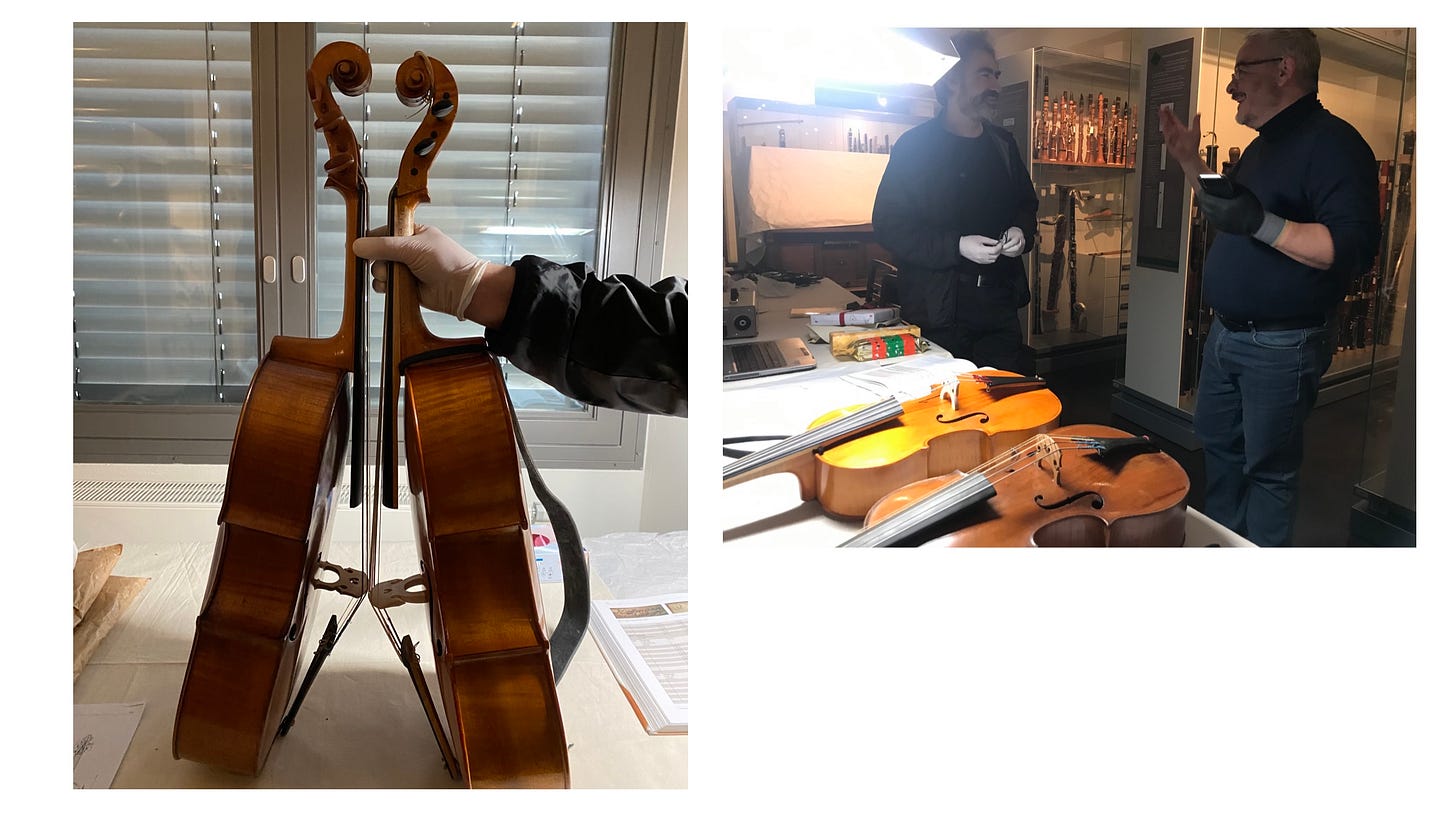

Varnish of Alessandro’s two instruments is done, they now just need a good rest before being fitted.

Featured video of the week

This week I want to share with you a beautiful Vivaldi concerto, played by one of the first enthusiasts of playing da spalla Jesenka Baltic Zunic. Enjoy!