Again from my notes about Mark Vanscheeuwijck’s lecture on violoncello piccolo.

One thing to consider is that the roots of today’s early music practice are in that revival movement which started post-WWII, thanks to people like Harnoncourt and later the Kuijken brothers (this list is kept too short on purpose). They started playing and researching from scratch, with a vague idea that things had to be done differently from how they were in the mid-20th century. They had few sources, no knowledge about strings manufacturing and even less about strings history.

Back then, they were mainly focalised on freeing the interpretation of 18th-century music from 19th and 20th-century practice, trying to be more faithful to the treatises.

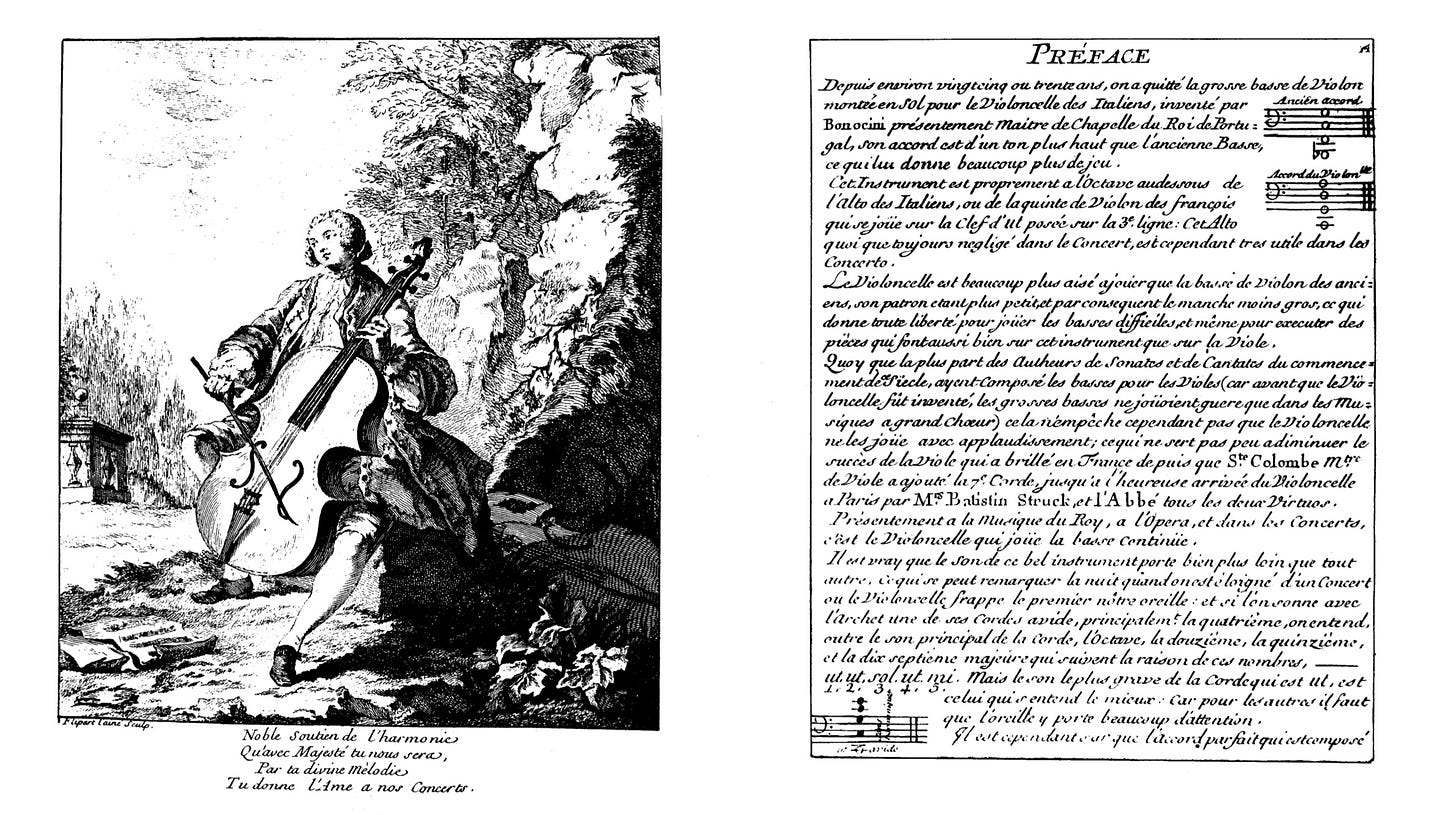

So it is perfectly natural that, concerning the cello, they looked back at the first treatise that mentioned the cello, which is Michelle Corrette, Paris 1740. And they took this as “the baroque cello”.

On this generally accepted idea, there are many considerations to bring to our attention.

The time: 1740 is not the “baroque period” anymore, rather, it’s stile galante, more towards classical.

Michelle Corrette was an organist and wrote tutorial books of all instruments (not treatises), addressed to the amateur players, so to the nobles men, those that could afford to buy books. Italy and Italian things were on fashion, so what he promotes is the style of the cellists who recently arrived in Paris from Naples (Lanzetti, Franceschiello...). He mentions Giovanni Bononcini, who travelled everywhere: from his hometown Modena to Rome, Naples, Paris, London, Portugal, Spain, Wien.

In Naples, they adopted a “standard” size cello which was midway between the Violone or bass violin and the smaller violoncino. The repertoire from Naples is a consort repertoire, operas and cantatas with often arias with an obbligato part for cello. They usually had 4 strings, but even 5 is possible (and suitable).

Instead, it’s from Bologna that we have repertoire for solo cello: recercare and sonatas, as well as some didactical collections, were published by the members of the Accademia di San Petronio: Domenico Gabrielli, Giuseppe Colombi, G. B. Vitali, Domenico Galli, the Bononcini brothers and more… in Bologna, they played (as standard for a violin family at the time in northern Italy and the German region) a larger violone and a smaller violoncino, and they played in all positions, vertically or horizontally, seated, standing or walking. If the Violone played the bass line, the smaller violoncino could play a harmonisation of the bass or a melody in it, or as well an obbligato part.

Musicians from the region of Bologna and Mantova travelled to all of the European courts: Austria, Germany, Portugal and Spain, bringing their repertoire and way of making music. (Caldara, Torelli, A. Vitali, E. F. Dall’Abaco). They arrived up to J. S. Bach, who used their small cello and called in his cantatas for a violoncello piccolo, to mean the smallest version of the violoncello possible.

In conclusion, a baroque cellist today, from what we now know, should be able to play several instruments, from an 8 or even 12-foot bass to very small cellos, with 4, 5 or even 6 strings, tuned with the bass in C, G, D or Bflat, and in every possible playing position, playing standing or seated, with bow grip underhand or overhand.

Baroque virtuoso music is that of the viola bastarda, with the use of the whole range of the instrument, from top high register to lowest bass, and based mainly on articulation. Or those “Partite sopra diverse sonate” by G. B Vitali for the violone (da brazzo).

Going on towards the galante style and the standardization of the cello size, we move to a cantabile style with embellishments (e.g. Boccherini -who, anyway, had two cellos of different sizes, one bigger and one smaller).

Moving away from M. V. notes, I am more and more convinced that the violoncello da Spalla was a thing. At least, we honestly cannot exclude it as an option. Was it bigger than ours? Yes, initially (and in Italy) yes. But when they had wound strings, they could tune to bass notes even smaller instruments to be able to play more virtuosic music. (And virtuoso music is something they were used to doing in a horizontal position, with violin technique.)

Playing a smaller bass not only added a different colour to an ensemble but also revealed a true “tenor” timbre of voice, very suitable for obbligato parts, dueting with singers.

There is actually not enough iconography with instruments like ours. M. V. Says it’s a fake also because tenors had lower ribs, like violas. But there are many surviving instruments in museums, so what were they? For sure there are still open questions. One of them is why Bach’s region’s pomposas were so small (Hoffmann, Snoeck, Wagner, Hunger, etc…) when compared with Italian iconography.

Updates from our workshop

Back at the bench, Daniela is concentrating on the “set up” parts. Fingerboard and tailpiece are handmade from scratch, by pieces of different woods glued together and shaped. It’s time-consuming, but this is how things are done in lutherie.

As you see, Alessandro is going on with his viola.

Featured video of the week

I recommend this video interview of Mark Vanscheeuwijck by Elinor Frey, as there are a lot of sources and iconographies, as well as food for thoughts.